In the fitness industry, everyone’s obsessed with “more”. More cardio. More squats. More gym time. More calorie restriction. But if you’re not careful, “more” can lead to overtraining, injury, and illness. Here’s how to know what’s TOO MUCH when it comes to exercise.

I’ve been coaching clients for nearly 25 years and I’ve seen many of them treat their bodies like teenagers learning to drive a car.

Vroom.

Full speed ahead on killer workouts! Max effort each time! Add another hour of cardio!

Errrt!

Get hurt. Get sick. Feel discouraged.

Vroom.

Cut calories! Weigh and measure everything!

Errrt!

Lose control. Feel even more discouraged.

We see this cycle of alternatively slamming the gas, then brake, then gas, then brake with our Precision Nutrition Coaching clients.

When they decide to get moving, they go hard.

They throw everything — energy, time, resources — at their their weight loss, strength gain, or health goals. They feel invigorated and energized, high on their new workout drug.

Have you tried Workout X? they ask their coworkers.

Feel my quads, it’s amazing!

This full throttle approach seems to work for a little while.

Until… it doesn’t.

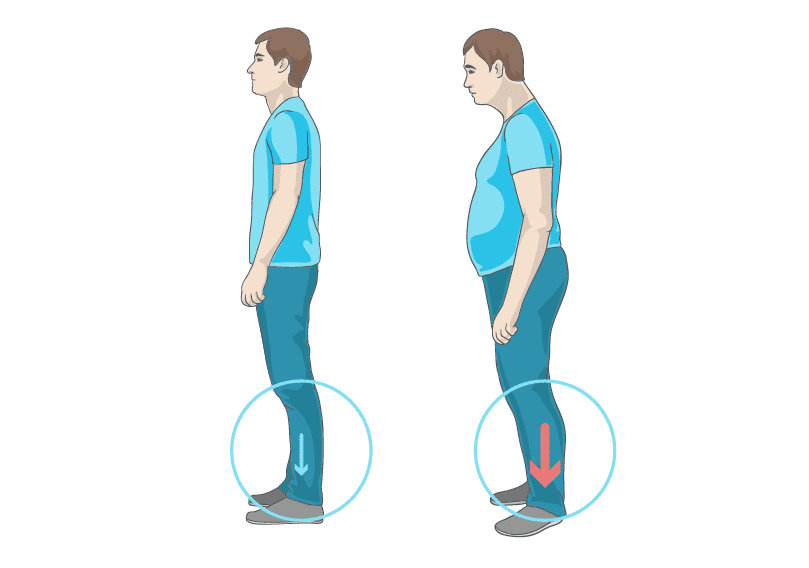

One day it’s hard to get out of bed. Shoulders and knees ache a bit. They get a bit of a cough or feel run down.

A week later they miss an easy lift. They reach for the ice pack. No big deal.

The week after, they’re dialing their chiro or physio’s office. Or lying on the couch with a back spasm that feels like giving bellybutton birth to a sea urchin.

What happened? Where did it all go wrong?

The problem isn’t the exercise, or even the intensity.

The problem is not balancing stress with recovery.

Training vs. straining.

Exercise is a stressor. Usually a good one. But a stressor nonetheless.

If you exercise intensely and/or often, you add stress to a body that may already be stressed from other life stuff like work, relationships, travel, late nights, etc.

This isn’t a bad thing. Exercise can indeed help relieve stress.

But in terms of a physical demand, we still need to help our bodies recover from all the stress we experience.

How well you’ll recover (and how much extra recovery you might need) depends on your allostatic load — i.e. how much total stress you’re under at any given moment.

In other words, those days when you were late for work and your boss yelled at you and you spilled ketchup on your favorite shirt and you were up all night caring for a sick child — and then you went to the gym and tried to nail a PR?

It’ll take longer for you to recover from that workout than it would have if you’d done it on a day you slept well, woke up to sunshine, and had a terrific breakfast.

The right amount of exercise, at the right intensity, and the right time:

We train. We learn. We get healthier and stronger.

Too much exercise, with too high an intensity, too often:

We strain. We stress. We shut down. And break down.

Mission Control: Our bodies.

Overtraining isn’t a failure of willpower or the fate of weak-minded wimps. Our bodies have complex feedback loops and elegant shutdown systems that actively prevent us from over-reaching or pushing ourselves too hard.

Two systems are at play:

- Our central nervous system (CNS) acts like a car engine regulator. If the engine on a car revs too high for too long, it shuts down. Similarly, if we exercise too much, our brain tries to protect our muscles by reducing the rate of nerve impulses so we can’t (or don’t want to) move as much. And we certainly can’t work as hard.

- Local fatigue, the result of energy system depletion and/or metabolic byproduct accumulation, makes your muscles feel really tired, lethargic, and weak. Using our car analogy, this is sort of like running out of gas.

Training too frequently and intensely — again, without prioritizing recovery — means that stress never subsides.

We never get a chance to put gas in the tank or change the oil. We just drive and drive and drive, mashing the pedals harder and harder.

If we “lift the hood” we might see:

- Poor lubrication: Our connective tissues are creaky and frayed.

- Radiator overheating: More inflammation.

- Battery drained: Feel-good brain chemicals and anabolic (building-up) hormones have gone down.

- Rust: Catabolic (breaking-down) hormones such as cortisol have gone up.

As a result, you might experience:

- Blood sugar ups and downs.

- Depression, anxiety, and/or racing thoughts.

- Trouble sleeping or early wakeups.

- Food cravings, maybe even trouble controlling your eating.

- Lower metabolism due to decreased thyroid hormone output.

- Disrupted sex hormones (which means less mojo overall, and in women, irregular or missing menstrual cycles).

Here’s the thing.

You don’t get to decide if you need recovery or not.

Your body will decide for you.

If you don’t build recovery into your plan, your body will eventually force it.

The more extreme your overtraining, the more you’ll “pay” via illness, injury, or exhaustion. The more severe the payback, the more “time off” you’ll need from exercise.

That’s a bummer. Now your car has stalled, or worse — gone backwards. Argh.

What drives people to overtrain?

Some folks in our Precision Nutrition Coaching program worry that the prescribed workouts and daily habits won’t be enough. So they add more exercise and subtract food.

What’s driving them?

1. Some depend on intense exercise to feel good about themselves.

They might tell themselves it’s “for their health” or “to get the perfect body”.

But, the truth is, many people depend on their extreme exercise regimen to feel good about themselves.

Take this client story from Precision Nutrition Coach Krista Schaus:

Early on in the program, a client’s weight went up a few pounds on a particular measurement day. I went on high alert.

I called her and could hear the treadmill rolling in the background. “Uh, what are you doing… right now?”

Turns out she was into her 40th minute of a 60 minute “post-measurement day guilt workout”.

I yelled, “Get off the *&%! treadmill… Now!”

Right then and there we made each other a promise: No more extra work. PN training program only.

She was terrified of eating more and doing less. But, after her first week of “eating more and doing less”, she lost 3 pounds.

(Before, she had been doing “everything right” and not losing a pound.)

A few months later, she’d lost 10 pounds and 6% body fat. She looked healthy, fit and amazing. People would ask for her secret.

Those intense, laborious workouts can feel good. Almost… too good.

Strenuous exercise releases chemicals that kill pain and make us happy… temporarily.

By the way, these chemicals are also released when your body thinks you’re in big trouble and about to die. Their evolutionary job is to help us float away in a happy painless haze as the saber-toothed tiger is eating our arm off. So in a sense, they’re stress-related chemicals.

For some people, these chemicals become a “hit”.

Pushing their bodies to the limit and working hard becomes their drug.

2. Intense exercise gives you a sense of control over your body and life.

It’s drilled into people’s heads via popular media: If you want control over how your body looks, hit the gym (and then hit it again).

Here’s another client’s story, in their own words:

I ran 7 marathons over the course of about 10 years, each time hoping that this training round would be the one that got me thinner.

But the harder I worked, the more frustrated I got. Which I used to propel myself harder, over more miles.

The more I trained, the hungrier I was. It was a massive battle against appetite, all day long.

I never got thinner. Sometimes I gained.

I got stressed out, cold after cold after random infection, and increasingly unhappy with myself.

For me, what I needed to finally drop those last 5-10 pounds wasn’t exercise for 1-2 hours a day, it was to go harder for shorter periods of time, and give myself enough downtime to recover.

It became so much easier to achieve a slight energy deficit when my body felt more at-ease, less pushed to the limits all the time.

Muscles stayed and got stronger. Fat shrunk away.

People who overtrain often want to try hard and do their best to reach their goals. They think they’re “doing what it takes”.

If some exercise is good, more must be better, right?

3. Most people don’t know that overtraining can work against them.

Precision Nutrition clients who are overtraining are often shocked to learn they’re doing too much. Nobody’s ever told them that there’s a “sweet spot” for exercise that balances work and recovery.

Usually, people learn about the risks of overtraining the hard way — like this client from our men’s coaching program:

Last week I injured my ribs and back. Not enough to put me out of commission, and it’s not serious, but it was a real pain in the a$s.

Certain positions and actions (like sneezing) felt like a knife in my side. I had to cut certain exercises out (e.g. push-ups), and I couldn’t jump rope or sprint, either.

I still did the workouts every day, but I had to cut back on the weight (I used about 80% of what I typically use), and for the intervals, scale back the intensity.

Now here’s the interesting part: When I was done with the workouts, I felt really good, as opposed to the fall-on-the-floor wiped out feeling I usually have. And I wasn’t sore the next day either.

In fact, I’ve been really looking forward to these workouts.

I thought: Hey, this is fun!

But then I had this other nagging thought: Am I just a wimp?

Anyway, all this got me thinking: What the hell am I working out so hard every day for? Should I be killing myself?

I’m not a competitor. Nobody knows or cares how fast I run or how much I squat.

I’m starting to think I should be ending a workout feeling like “I could do that again right now if I had to.” I call that “training”.

The opposite would be pushing myself to the limit frequently, feeling completely pooped after a workout. I call that “straining”.

It seems pretty obvious I won’t make a lot of fast progress by “training”, but on the other hand, I gotta wonder: How long can I keep going if I am “straining”?

Notice that this concept of training vs. straining is a true revelation to him!

Sometimes, less is more.

Putting in a consistent good effort over the long haul is much more sustainable than cycles of “crash and burn”.

This client’s slow and steady efforts paid off — he lost 20 pounds and 10 percent of his body fat in 6 months.

More importantly, he recovered, stayed uninjured, and kept having fun.

Do what truly works.

Look, if “pump till you puke” and hours of treadmill torture worked, we’d make our clients do it.

But it doesn’t work.

So we don’t do it.

Exercise should make us feel, look, perform and live better… not crush us.

Movement should help us function freely… not incapacitate us.

What if you could leave the gym feeling energized, not exhausted?

What if, instead of doing more, you could do better?

Recovery: Overtraining antidote.

Here’s your first tip: “Overtraining” isn’t exactly the problem.

The problem is more like “under-recovering”.

Your body can actually handle a tremendous amount of work… if you recover properly and fully from that work.

Your stress-recovery pattern should look like rolling hills: For every up (training or life stress) there’s a down (recovery).

For every intense workout, there’s an equally intense focus on activities that help your body repair and rebuild.

This doesn’t mean you need to retreat to your dark and quiet blanket fort and get massages every day… although that does sound awesome.

Check out our recovery tips below.

Free your mind, and your body will follow.

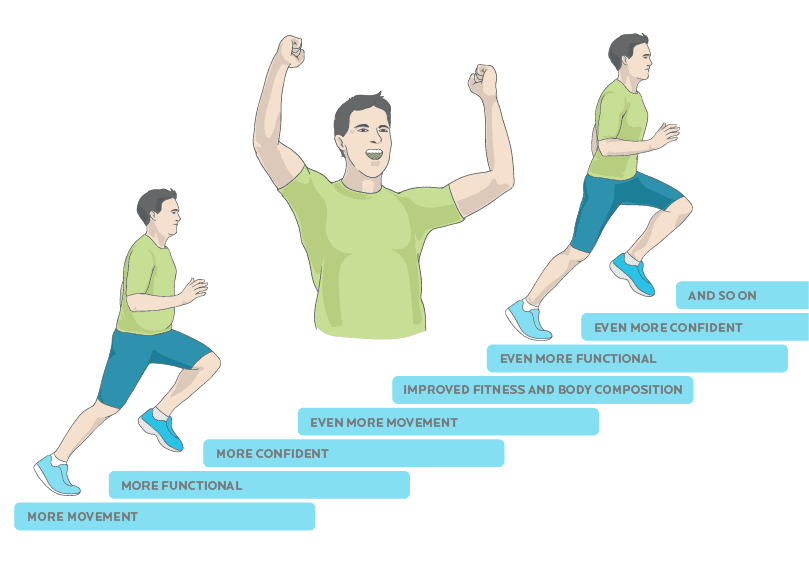

When you factor in recovery as a crucial part of your training regimen, a funny thing happens.

You start to think of training completely differently.

What if you could “exercise” on a continuum — where every movement “counts”?

What if you could balance high with low, heavy with light, work with play in a natural, organic rhythm?

Here are some ways to find balance.

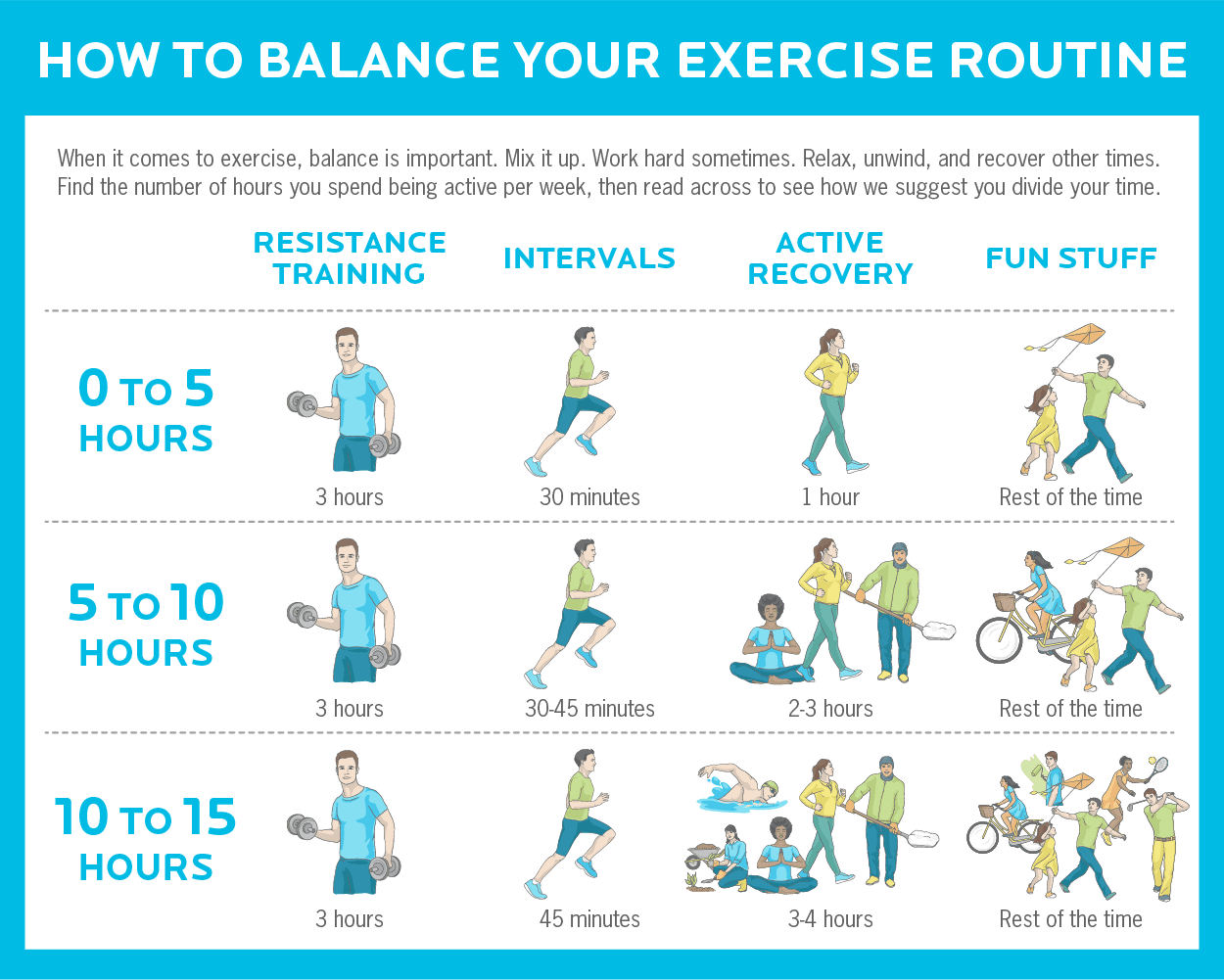

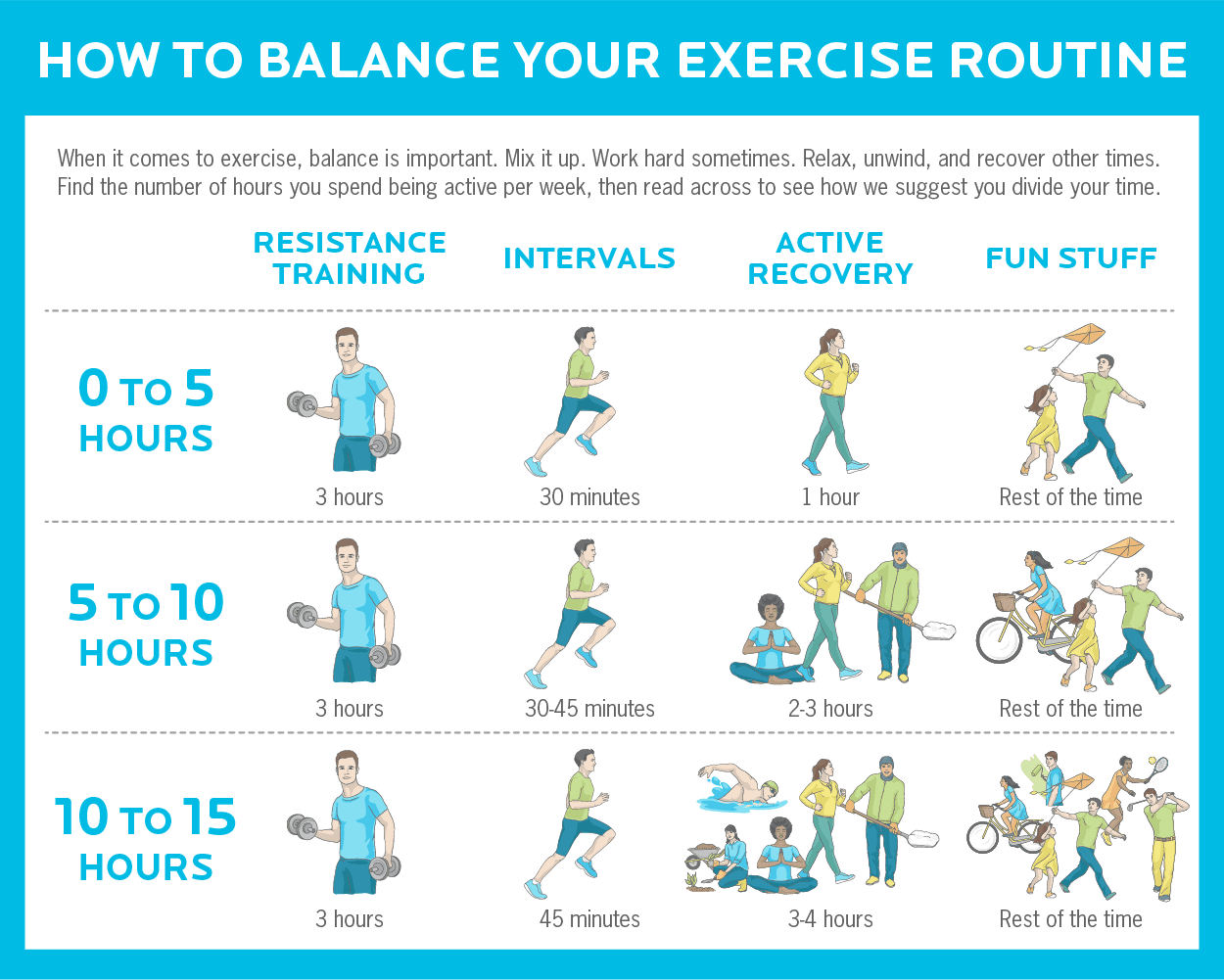

An effective physical activity routine incorporates:

- Resistance training

- Intervals

- Active recovery

- Fun

You can do that no matter how much time you have to devote to physical activity.

Here’s what the balance looks like in Precision Nutrition Coaching:

Precision Nutrition Coaching clients who have the most success aren’t usually the ones who do the biggest, most challenging workouts.

Instead, they’re the ones who find small ways of getting movement whenever and wherever they can.

That includes real-life functional movement, such as:

- Biking or walking to work (or running to catch that damn bus)

- Walking to the grocery store and carrying your groceries home

- Washing the car

- Giving the walls a fresh coat of paint

- Teaching your kids how to fly a kite

- Shoveling snow, raking leaves, planting a garden, or mowing the lawn

When you think of movement this way, it stops becoming “a workout” (i.e. a chore, or a gauntlet you have to psych yourself up for) and starts becoming “your daily life” (i.e. something that is easy, seamless, and always with you).

What to do next.

If you’re feeling some of the symptoms described in this article, here are a few steps you can take to start feeling better.

1. Do a little self-assessment.

For some of us, skipping a workout is no biggie.

For others, taking a day off requires effort. Doing less can make you feel uneasy.

If spending more time away from your self-imposed bootcamp freaks you out, ask yourself:

- What are you doing this for? What are your actual goals, and why?

- How do you feel? Are you constantly in pain, tired but wired, hungry, etc.?

- How is what you’re doing working for you? Are you getting results?

If you’re beating yourself up and not getting anywhere, maybe it’s time to take a different approach.

2. Trust your body — and listen to it.

What’s really going on under the hood?

Do a mind-body scan: Lie quietly for a few minutes and bring your focus slowly from your feet to your head. What do you feel?

Practice becoming more aware of your body cues.

What does your body feel like when it’s well-rested? How do you know when it needs a break?

If you’re feeling:

- achey and creaky

- run-down and blah

- un-motivated

- anxious or depressed

- fatigued or annoyingly sleepless…

…consider changing up your workout routine.

3. Make time for recovery.

Recovery won’t happen by accident. Plan it, prepare for it and hunt it down.

Schedule that massage. Tell your friends to save the date for the citywide scavenger hunt. And block off Sunday afternoon for guilt-free goof-off time.

Whatever you do, remember that your recovery — what you do between workouts — is just as important as training.

Some ideas:

- Go for a walk, preferably in a natural, outdoor setting. Put away your phone. Observe what’s around you.

- Meditate. It’s easier than you might think.

- Do yoga. Remember: it doesn’t have to be ‘hot yoga’ or ‘power yoga’ to count.

- Go for a swim. Finish it off with a relaxing sauna.

- Chill out in the park. Lie back on the grass and stare at the clouds.

- Get a massage. Give the body a little help de-stressing.

- Get it on. Yep, sex counts too. (Thanks, Precision Nutrition!)

4. Achieve the balance.

There’s time for tough workouts and time for taking it easy. There’s time for long runs, and there’s time for throwing a frisbee around.

Doing the same thing over and over again isn’t doing your body any good. Mix up your exercises, and the intensity.

If you’re not sure how much of each you’re getting, try keeping a workout journal for a week or two.

What could you use a little more of?

Where could you ease back?

Find some new ways to get active without being in the gym.

Incorporate some silly, goofy play time into your routine. See how it feels.

5. Have fun.

And there’s a reason why kids naturally run, jump, roll, and wiggle their bodies around: Fun is a huge part of how we learn to move and interact in the world. Continuing this process keeps us healthy and young.

Laughing activates the recovery system, as does even just smiling. Lighten up and loosen your white-knuckle grip on life, Sergeant Hardcore.

Here are some ideas for good old-fashioned fun:

- Play a sport you love. Or discover a new one.

- Actively play with your kids. Run around with them on the playground, swing from the monkey bars, climb trees, chase a frisbee, etc.

- Dance. Have a night out with friends, or just goof off with the music cranked up in your living room.

- Pay your pet some extra attention. Give your dog an extra run for his money at the dog park. Try some kitty yoga. (This is a thing. I’m not even kidding.)

- Go for a hike or take a walk in the city. Explore a new neighborhood.

6. Get driving lessons.

The only message you’ve likely ever gotten about staying fit is: put the pedal to the metal. Now it turns out you’re actually in overdrive?

If you’re feeling frustrated or confused (or exhausted or stressed) — team up with someone.

Find an active friend, an interested spouse, a parent you want to spend more time with, or a local trainer/coach/sensei. Together, experiment with a fun, balanced approach to your physical activity.

Your “car” will thank you.

For full article by John Berardi please visit: http://www.precisionnutrition.com/are-you-overtraining