Take a look at the article below to find out why you may have hit a plateau with your weight loss or training!

http://www.precisionnutrition.com/metabolic-damage

Take a look at the article below to find out why you may have hit a plateau with your weight loss or training!

http://www.precisionnutrition.com/metabolic-damage

In the fitness industry, there are many misconceptions about the sport, says Tim Geromini, C.S.C.S., a strength and conditioning coach at Cressey Performance, who regularly works with professional baseball players. “Baseball has historically not been looked at as a sport that trains with the same intensity as others.”

But Geromini takes a contrarian’s view: “Baseball players are extremely hard workers,” he says. Don’t believe him? Take Mike Trout’s need for speed; Bryce Harper’s insane balance and strength; or Jose Altuve’s fierce dedication to an exercise routine.

The sport is no walk in the park: “Throwing a baseball is the single fastest motion in all of sports,” he says. And an exercise program designed to help you sprint fast or react quickly isn’t enough. That’s why top trainers incorporate something else: medicine balls.

“Medicine ball training, when done correctly, is the biggest thing we can do in a gym setting that replicates a baseball player’s movements on the field,” says Geromini. The technique can work for you, too. After all, the goal is similar: “to be athletic, explosive, and powerful.”

To get there, complete the below workout from Geromini—which will challenge your core, arms, glutes, shoulders, and hips—before your typical weight lifting session twice a week. Leave a few days in between sessions.

Day 1:

(1) Overhead Medicine Ball Stomp to Floor: Using an 8- to 12-pound medicine ball, reach arms straight overhead, get tall, keep your core tight, squeeze your glutes, and slam the ball as hard as you can to ground. Complete 3 sets of 8 reps.

(2) Supine Bridge March: Lay on your back, legs bent, feet flat on ground, lift to a bridge position with butt in the air. One leg at a time, lift knee toward head and squeeze butt, switch legs. Complete 3 sets of 6 reps per side.

(3) Rotational Medicine Ball Scoop Toss to Wall: Using a 6-pound medicine ball, stand a few feet from the wall, arms down by side. Load into back hip as if you are swinging a bat, and rotate through upper back. Throw the ball against the wall as hard as you can with arms down (a scoop motion), finishing as if you swung a bat. Complete 3 sets of 8 reps per side.

(4) Mini Band Side Steps: Place a mini band above your knees. With feet underneath your hips, take a step out with your left leg making sure you press out against the band and your knees don’t cave in, your right leg follows. Repeat each direction 8 times. Complete 3 sets per side.

Day 2:

(1) Recoiled Rollover Med Ball Stomp to Floor: Using an 8-pound medicine ball, start with arms by your side. Lift the ball overhead by rotating around your side like a windmill. Once you reach the highest point, get tall, squeeze glutes, slam ball as hard as you can. Then do the same on the other side. Complete 3 sets of 4 reps on each side.

(2) Bird Dog: Start in a quadruped position (on your hands, knees, and feet) with your back flat. Raise and straighten your right arm and left leg in the air without letting your body shift to the side or your back to arch. Come down and do the same thing on the opposite side. The goal of the exercises is to keep your core tight and squeeze your glutes. Complete 3 sets of 8 reps per side.

(3) Rotational Medicine Ball Shot Put to Wall: Using a 6-pound medicine ball, stand a few feet from the wall, arms up at shoulder height (think like a shot putter). Load into your back hip as if you are swinging a bat, rotate through your upper back, and throw the ball against the wall as hard as you can. Try to reach for the wall at the finish. Complete 3 sets of 8 reps on each side.

(4) Bear Crawls: Start on all fours on the ground (in a quadruped position). Lift knees off the ground and crawl forward with the right hand and left leg, then the left hand and right leg. Picture having a pot of coffee on your back—don’t let it spill. Complete 3 sets of 12 reps.

For full article by Cassie Shortsleeve, please visit http://furthermore.equinox.com/articles/2016/07/medicine-ball-baseball-workout?emmcid=emm-newsletter&utm_source=newsletter&utm_medium=email-member&utm_campaign=1025&cid=-Furthermore_102510252016

The backside has always been a statement piece, treasured by the ancient Dogos people in Mali, Renaissance painters, and rappers alike. And though consistently considered a key asset of the female — and at times male (Details magazine deemed the ass, the new abs in 2011) — physique, its desired proportions have shifted throughout history. Unfortunately, the elusive, sculpted posterior of 2013 takes work, but fortunately our experts have discovered the precise formula that delivers the tight, lifted, perfectly carved posterior of which international uproars are made.

Our equation starts with the five moves scientifically proven (by studies from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the University of Wisconsin, La Crosse) to target the glutes most effectively: lunges, single-leg squats, hip extensions, step-ups and side leg lifts. We then added a little complexity and dimension to each move by incorporating the principles of mobility and stability characteristic of all Equinox programming. Finally, we applied the trusted NASM training philosophy that mandates a combination of strength and power-based exercises. Together, it’s a plan that just screams results.

“I wanted to build on the classic moves from the research, so each exercise in our workout is rooted in the biomechanical principles that make it effective,” says Lisa Wheeler, senior national creative manager for group fitness at Equinox who developed the program. “I just turned up the intensity a few notches by creating four pairs of one controlled, purely strength-based move with a more dynamic, power-based exercise, which is a much more efficient way to train.”

Watch Wheeler’s workout in the video above, modeled by LA-based group fitness and Pilates instructor Christine Bullock at the rooftop pool at The London Hotel in West Hollywood. Then, click through the slide show below for step-by-step instructions. Your circuit: Do 10-12 reps of each strength move, and 45 seconds of each power move resting for 30 seconds between each pair. Repeat 3 times.

To view full article by Furthermore Editors, please visit http://furthermore.equinox.com/articles/2013/02/butt-workout?emmcid=emm-newsletter&utm_source=newsletter&utm_medium=email-member&utm_campaign=0621&cid=-Furthermore_06216212016

To most people, healthy movement = exercise. As in cardio, crunches, and fitness models. But moving your body is about so much more, like improved thinking, stronger relationships, and expressing your purpose in life.

Sometimes, vanity.

Often, fitting into social norms.

“The man” telling you what to do (or how to be).

Moral righteousness packaged as 6am Hot Detox Spin-Late Pump class or an entire weekend of Instagram-worthy self-punishment.

But healthy movement is actually more interesting, liberating, and, frankly, crucial than all that.

In my years as a health and fitness coach, here’s the most important thing I’ve discovered: Developing a body that moves well is the ticket to a place where you feel — finally — capable, confident, and free.

It’s no secret: Human life has become structured in a way that makes it very easy to avoid movement.

We sit in cars on the way to work. At work we sit at our desks for much of the day. Then we come home and sit down to relax.

That’s not what our bodies are built for, so creaky knees, stiff backs, and “I can’t keep up with my toddler!” have become the norm.

Sure, if you can’t move well, it may be a sign that you aren’t as healthy as you could be. But the quality and quantity of your daily movement — your strength and agility — are actually markers for something much more important.

In my line of work, you watch a lot of people lose a lot of weight. The results would shock you — and I’m not talking about how they look on the beach in their bathing suits (although there is always a big celebration for that).

Most often, the thing people are most excited about after they go from heavy and stiff to lean and agile is this feeling that they’re now living better. They notice they’re:

They’re happier, but not just because they wanted to look better, and now they do. They’re happier because their bodies now work like they’re supposed to. They can now do things they know they ought to be able to do.

As humans, we move our bodies to express our wants, needs, emotions, thoughts, and ideas. Ultimately, how well we move — and how much we move — determines how well we engage with the world and establish our larger purpose in life.

If you move well, you also think, feel, and live well.

It’s proven that healthy movement helps us:

Shocking secret: There’s nothing magic about a resistance circuit, the bootcamp class at your gym, or the latest branded training method.

Our ancestors didn’t need to “work out” when they were walking, climbing, running, crawling, swimming, clambering, hauling, digging, squatting, throwing, and carrying things to survive. Nor did they need an “exercise class” when they ran to get places, danced to share stories or celebrate rituals, or simply… played.

“Working out” is just an artificial way to get us to do what our bodies have, for most of human history, known and loved — regular movements we lost and forgot as we matured as a species.

We may not hunt for dinner anymore, and we may opt for the elevator more often than not.

We may move less. But movement is still programmed into the human brain as a critical aspect of how we engage with the world.

Therefore, to not move is a loss much, much greater than your pant size.

While there are universal human movement patterns, our specific movement habits are unique to us, and to our individual bioengineering.

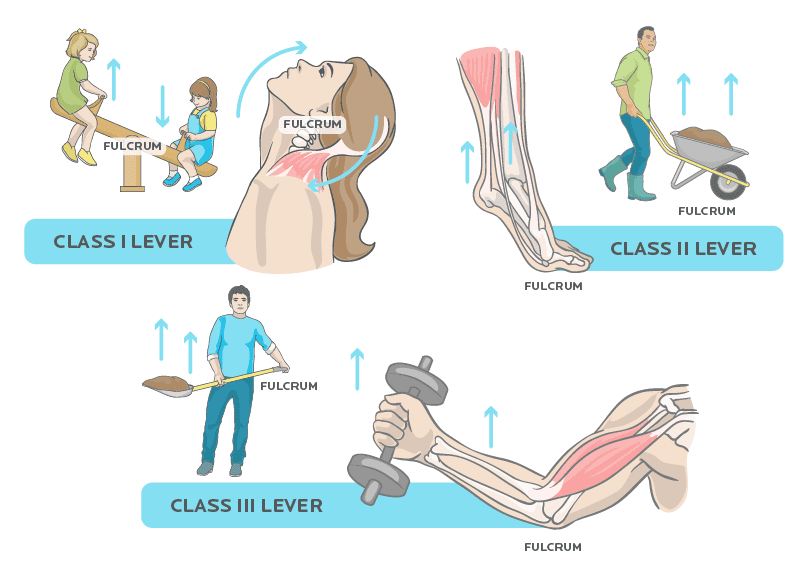

Basically, the human body amounts to a sophisticated pile of interconnected levers:

How you move is determined by the size, shape and position of all of those parts, along with anything that adds weight, like body fat.

If you’re a tall person with long bones it may be harder for you to bench press, squat, or deadlift the amount of weight your shorter buddy can, because your range of motion is much bigger than your friend’s, so you have to move that weight a longer distance with much longer levers.

(This is why there aren’t many super-tall weightlifters or powerlifters, and why great bench pressers usually have a big ribcage and stubby T-Rex arms.)

But you can probably spank your short friend at swimming, climbing, and running.

If you’re bottom-heavy and/or shorter, you may not be able to run as fast as your taller friend. But you may have exceptional balance.

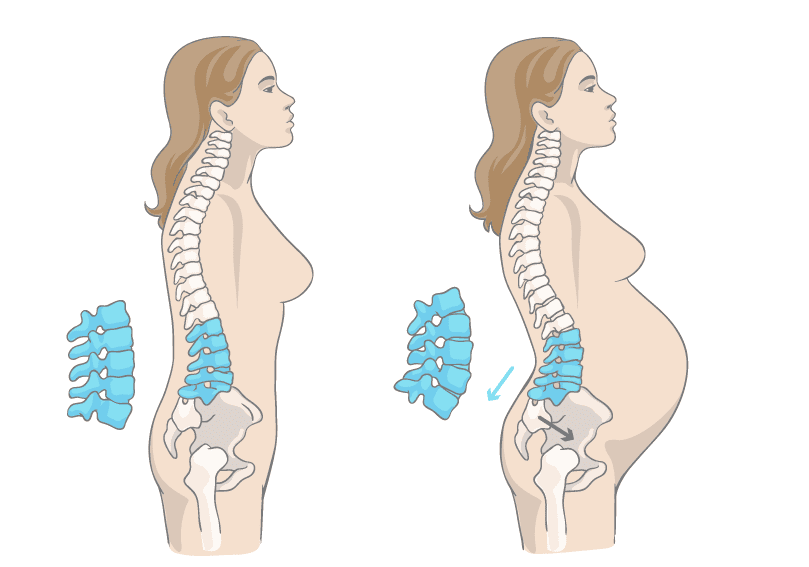

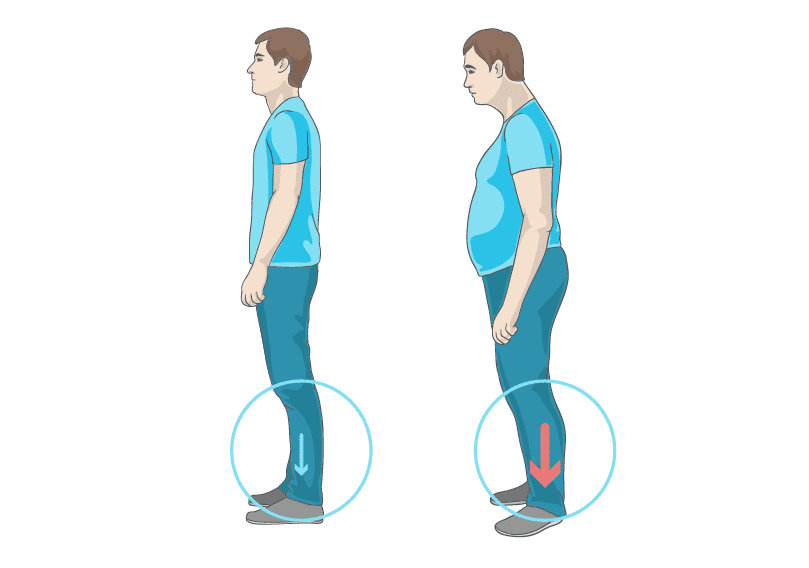

If you’ve gained weight in your middle (or if you’re pregnant), you may have back pain. That’s because the extra belly weight pulls downward on the lumbar spine (lower back).

When the lumbar spine is pulled down and forward (“lordosis”):

The downward pull can also affect all the joints below (the pelvis, hip, knee, and ankle).

Conversely, it also works in the opposite direction, where, say, ankle stiffness can affect movement in the lower back.

If you have wider shoulders (“biacromial width”), then you have a longer lever arm, which means you can potentially throw, pull, swim or hit better.

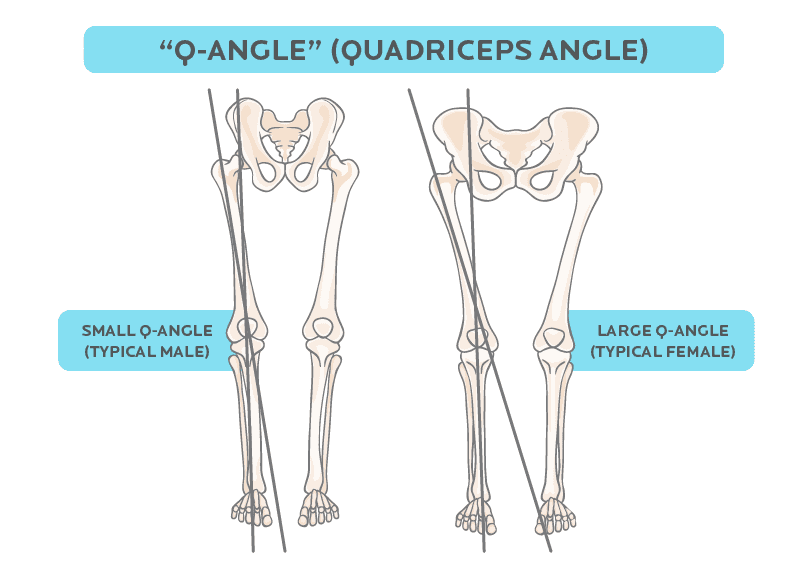

If you have longer legs, then you have longer stride, which means you can potentially run faster. This is especially true if you also have narrower hips, which create a more vertical femur angle (“Q-angle”), allowing you to waste less energy controlling pelvic rotation.

Some variations in movement, we are given by nature and evolution. Other variations, we learn and practice.

If you’re a woman who’s top-heavy, you may have developed a hunch in your thoracic spine (upper and mid-back), whether from the physical weight of your breasts or from the social awkwardness of being The Girl With Boobs in middle school.

Or, if you got really tall at an early age, you may have developed a habitual hunch to hide your size or communicate with hobbits like me.

Yet the structural engineering remains important. Especially if we understand how our structures and physical makeup affect our movements.

For instance:

This is especially true if you don’t have enough muscle to drive the engine.

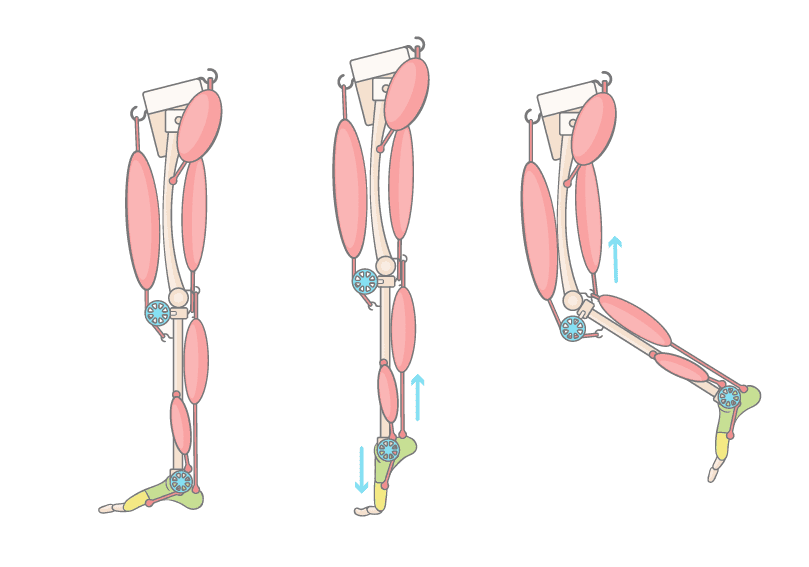

At a healthy weight, your center of mass is just in front of your ankle joints when you stand upright.

However, the more mass you have, especially if you have extra weight in front, the harder your lower legs and feet have to work to keep you from tipping forward.

This puts additional torque (rotational force) on ankle joints.

Once you start walking — which is, essentially, a controlled forward fall — you have to work even harder to compensate.

Any unstable or changing surface (stairs, ice, fluffy carpet, a wet floor), requires your lower joints to adjust powerfully and almost instantaneously — literally millisecond to millisecond.

As a result, obese children and adults fall more often.

Human bodies are amazingly adaptable and clever, but nevertheless, physics can be an unforgiving master.

The good news is that this is generally reversible.

When we move:

All of these (and a variety of other physiological processes) tell our bodies to use its raw materials and the food we eat in certain ways.

For instance, movement tells our bodies:

And improved body functions ensure you’ll be able to move well and:

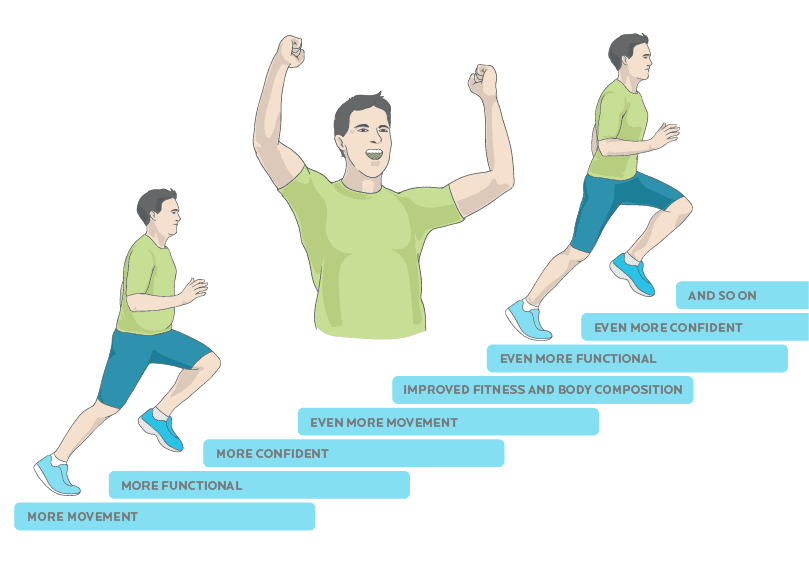

The more we can do confidently and capably, the fitter we’ll be. Even better, that means we’ll do more. That leads to more fitness. And this virtuous cycle continues.

Despite eyeglasses and iPhones, humans are still animals. We’re meant to move with the grace and agility of a tiger (or a monkey). And movement offers us a tremendous number of (sometimes surprising) benefits.

As babies, we immediately start grabbing things, putting things in our mouths, reaching for things, and clinging to our (now less furry) primate parents.

We are tactile, kinesthetic beings who must directly interact with physical stimuli: touching, tasting, manipulating, moving ourselves around objects in three-dimensional space.

Movement is a sensor for the world around us.

In one study, when people’s facial muscles were paralyzed with Botox, they couldn’t read others’ emotions or describe their own. We need to mimic and mirror the body language and facial cues of one another to connect emotionally and mentally.

From the puffed-chest posturing of drunken young men outside a bar, to Beyonce’s fierce dance moves, to the mating rituals like close leaning and eye contact, to the laser stare your mom gives you when she knows you’re up to no good:

Movement gives us a rich, nuanced expressive language that goes far beyond words, helping us build more fulfilling and lasting relationships, with fewer misunderstandings, disconnections, or communication bloopers.

You might imagine that “thinking” lives only in your head.

But in reality, research shows we do what’s called “embodied cognition” — in which the body’s movements influence brain functions like processing information and decision making, and vice versa.

So “thinking” lives in our entire bodies.

But even if thinking were limited to our brains, there is evidence that movement and thought are intertwined.

It turns out that the cerebellum — a structure at the base of the brain previously thought to only be used for balance, posture, coordination, and motor skills — also plays a role in thinking and emotion.

Also, movement supports brain health and function in many ways, by helping new neurons grow and thrive (i.e. neurogenesis).

Every day, our brains produce thousands of new neurons, especially in our hippocampal region, an area involved in learning and memory. Movement — whether learning new physical skills or simply doing exercise that improves circulation — gives the new cells a purpose so that they stick around rather than dying.

Thus, movement:

Move well, move often, get smarter.

People of all shapes and sizes say they have a better quality of life, with fewer physical limitations, when they are physically active.

If you exercise regularly, you probably know that kickass workouts can leave you feeling like a million bucks. (Personally I think of mine as anti-bitch meds.)

Research that compared exercise alone to diet alone found:

People who change their bodies with exercise (rather than dieting) feel better — about their bodies, about their capabilities, about their health, and about their overall quality of life — even if their weight ultimately doesn’t change.

(Now… just imagine if you combined the magic of exercise with brain-boosting and body-building nutrition!)

Not everyone has to be (or can be) a ballet dancer or Olympic gymnast. As a 5-foot, 40-something woman who can’t run well nor catch a ball, I’m fairly sure the NBA and NFL won’t be calling me.

But I’m also not saying that, “Well, guess I shouldn’t climb the stairs because of my Q-angle” is the way to go.

I’m saying: Today, pay special attention to how you move.

Be curious.

As you go through the mundane activities of your day, notice how your unique body shapes your movements.

How do you move… and how could you potentially move?

In our coaching programs, we work with a lot of clients who have physical limitations, such as:

You may have some body configuration that makes it easier or harder for you to do certain things.

We all have structural or physical limitations. We all have advantages. It all depends on context.

Regardless of what your unique physical makeup might be, there are activities that can work for you, and help you make movement a big part of your daily life.

Ask yourself:

How can I move better — whatever that means for MY unique body? And what might my life be like if I did?

And finding someone who can help you if you think that’s what you need.

“Sense in” to your body:

Do you feel confident and capable? Ninja-ready for anything?

Do you have some physical limitations? Do you have ways to adapt or route around them?

When was the last time you tried learning new movement skills?

What movements would you like to try… in a perfect world?

If you’re working out a certain way because you think you “should”, but it’s not fitting your body well, consider other options.

Or, if your current workout is going great but you’re curious about other possibilities, consider expanding your movement repertoire anyway.

Everything from archery to Zumba is out there, waiting for you to come and try it out.

Remember: You don’t have to “work out” or “exercise” to move. And you don’t need to revamp your physical activity overnight, either.

Take your time. Do what you like. Pick one small new way you can move today — and do it.

Quality movement requires quality nutrition.

And just like your movements, your nutritional needs are unique to you.

Here’s how to start figuring out what “optimal nutrition” means for you:

If you feel like you need help on these fronts, get it.

A good fitness and nutrition coach can:

For full article by Krista Scott-Dixon, please visit http://www.precisionnutrition.com/healthy-movement

I gave it another shot this summer, with a twist: I was going to try neurosculpting. Lisa Wimberger, who runs The Neurosculpting Institute in Denver, created it when she felt like traditional meditation wasn’t doing enough for her. The premise is that you create a new automatic processes in your brain so that when something stressful happens, you react calmly instead of going into fight-or-flightpanic. And you do that by repeating a specific mental exercise a few times a week. “The brain can be reshaped with repetition,” says Wimberger. “So I realized you could actually train your brain to respond differently to stress.”

Wimberger’s process is explicated on her guided lessons, so I followed along every day for two weeks.

Neurosculpting 101

It starts out like most mindful meditations, prompting you to sit quietly and focus on your breath. This calms your nervous system and sets you up for the next phase, which is when Wimberger suggests bringing your attention to random places on your body (your fingertips, the back of your eyelids). “I want to get your curiosity going, which activates your prefrontal cortex,” she says. “That’s the area used when you retrain your brain, so activating it gets you ready to unlearn an old automatic thought process and learn a new one.”

Now that I’m in the right mindset (relaxed with blood flow and oxygen heading into the prefrontal cortex), it’s time to get to the meat of the session.

The session wraps up with two smaller tasks: Take your non-dominant hand and tap wherever on your body you feel lighter and give the experience a one- or two-word name. “You want to give yourself a way to recall that moment when you released the negativity,” Wimberger says. “If you do the neurosculpting exercise regularly, you’ll be able to just tap that area of your body or think of the words and you’ll instantly feel calm and free.”

Does it Hold Up?

While Wimberger has a lot of solid-sounding reasoning behind neurosculpting, she’s not a neuroscientist or a licensed clinical psychologist. Plus, there haven’t been any studies on the process to back up her claims. To find out more, I talked to David Victorson, Ph.D., an associate professor at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine and associate director of research at the Osher Center for Integrative Medicine in Chicago. “I see elements of mindfulness, hypnosis, visualization, guided imagery, reconditioning all integrated together, so it sounds like she’s come up with a new way to package some pretty standard practices,” he says. “And that’s not necessarily bad! If you put a fancy label on plain old water and it gets people to drink more, that’s still a good thing.”

Wimberger’s reasoning is also based on solid research. “You can absolutely retrain your brain and create new neural pathways,” says Victorson. “Our brains are plastic and training in mindfulness and meditation can have a profound effect on the way you think.” Even the tapping part—which is when I felt the oddest—has a purpose. “That is something done a lot in hypnosis,” says Victorson. “It gives you a cue that can instantly take you back to how you felt during your session.”

Final Verdict

Did I finally become the daily meditator of my dreams? Not exactly. But I have managed to do this a few times a week and I’ve noticed something interesting. I’ve become a lot more aware of how much control I have over my reactions to stress. It’s as if a speed bump has gone in so that when something bad happens, I don’t automatically feel panic and loss-of-control.

One morning I received an email from an editor full of last-minute interviews I needed to conduct urgently. When I started getting that pit in my stomach about how I was going to squeeze it all into my already-packed day, I took a deep breath and imagined the pit in my stomach flowing out of my body into my magical steel box. I really felt lighter and was able to calmly start contacting sources for that story. It’s not that I can will myself into instant Zen, but with practice, it might happen even for me. So if you see me on the subway tapping on my stomach, you’ll know I’m really training my brain.

For full article by Alice Oglethorpe please visit http://furthermore.equinox.com/articles/2016/08/can-you-train-your-brain?emmcid=emm-newsletter&utm_source=newsletter&utm_medium=email-member&utm_campaign=0811&cid=-Furthermore_08118112016

Our modern digital age has brought us many conveniences. BlackBerry devices, iPhones, tablets and e-readers allow us to communicate and be entertained with the push of a button. Technology can improve our quality of life, but it comes with a price: being huddled over devices for long period of times can do more harm than good.

Using certain devices for extended periods of time can easily lead to neck strain, headaches, and pain in the shoulders, arms and hands. Anyone who has used a cellphone or tablet for an extensive amount of time has probably experienced the peculiar strain it puts on your upper body. These conditions even have their own name now: Text Neck.

Here are some simple strategies to help shut down text neck strain:

Taking frequent breaks and looking up from your device can provide your neck with some relief from the pressure of looking down.

It is important to sit up straight while texting. This way you can maintain good posture, relieving your back and shoulders from the strain of being hunched over.

Holding the phone closer to eye level helps maintain a healthy posture and puts less strain on the neck.

Be sure to stretch often between long periods of extended use of devices. You can rotate your shoulders with your arms by your sides to relieve tension. You can also tuck your chin down to your neck and then look up – this helps to relieve some of the tension in your neck built from the common forward-down position you adopt when looking at your device.

The plank is still a no-fail core-strengthening move, but if you want it to work harder for you, you must get creative. For example, when New York City-based Equinox trainer and instructor Alicia Archer, who has a BFA in dance from Fordham University and The Ailey School, realized that she could use specific plank variations as a way to better prepare her clients to transition into handstands, she knew she’d struck gold. “Planks have been around forever. It’s really how you tackle them that will make a difference,” says Archer. “A lot of the strength conditioning and proper technique required to perform handstands can be accessed by plank work, allowing you to build from the ground up.” These moves in particular will help you develop scapular protraction, engage your core (creating a stronger ‘wrap’ around your midsection), open up your hips, activate your glutes and improve your flexibility—all while testing your mobility, balance and stability.

Perform up to 3 sets of this workout (with a 30-second rest between each), focusing on your form, alignment and breath, rather than quantity or speed.

1. Flexed Knee Hip Extension

Start in plank position (palms under shoulders, legs extended behind you, back flat, abs engaged). Lift right leg until it’s parallel to the floor, and then bend knee. Keeping toes pointed toward the ceiling, engage glutes and lift leg up a few inches; lower. Pulse up and down for 8 to 10 reps; switch legs and repeat.

2. Inverted Hip Extension With Push-up

Start in plank position (with legs extended or knees down on floor). Extend left leg diagonally toward ceiling, and then bend elbows by sides, lowering chest to floor. Push back up and press back, lifting hips into a 3-Legged Dog (body in an inverted V position). Do 8 to 10 reps; switch sides and repeat.

3. Thoracic Extension with Hollow Hold

Lie facedown with palms on floor under shoulders, head and chest lifted, back slightly arched, legs together and extended behind you. Starting the movement from your core, lift body into plank position and round back slightly toward ceiling. Slowly return to start. Do 8 to 10 reps.

4. Diagonal Knee Pulls

Start in plank position. Rotate torso to left as you bring right knee in toward left elbow. Repeat, rotating torso to right as you bring left knee in toward right elbow. Do 8 to 10 reps.

5. Double Leg Hop & Float

Stand with feet and legs together. Hinge forward from hips and place palms on floor, a few inches in front of your shoulders. Press into palms, bend knees, and then hop both feet up, bringing knees in toward chest, lifting feet toward ceiling, keeping upper body in a straight line. Squeeze knees closer in to chest. Gently lower back to start. Do 8 to 10 reps.

6. Knee Slides

Start in plank position. Bring right knee up beside right wrist. Keeping toes pointed, abs engaged and back flat, “slide” knee all the way up side of your arm, until you reach shoulder level. Slide back down and repeat. Do 8 to 10 reps; switch sides and repeat.

For full article by Lindsey Emery please visit http://furthermore.equinox.com/articles/2016/08/planks?emmcid=emm-newsletter&utm_source=newsletter&utm_medium=email-member&utm_campaign=0811&cid=-Furthermore_08118112016

Long distance runners are on board; our experts discuss the implications for gym-goers.

In an age of legalization, edibles, and medical marijuana cards, pot’s pushing its way into the health and wellness space: Runners are preaching the powers of pot and professional athletes are endorsing its use in recovery. It seems everyone knows someone who tokes and takes fitness seriously.

Scientific literature on the topic of marijuana and exercise, however, is slim. Since the U.S. government still classifies marijuana as a schedule I drug, it’s hard to study; and only in the past few years have some of weed’s positive health implications become more widely accepted and reported.

But there actually are anecdotal reports that weed can enhance athletic performance, says Arielle Gillman, a researcher at the University of Colorado–Boulder who recently co-authored an article on the topic. “These reports come from all kinds of exercisers—including endurance runners, rock climbers, weight lifters, and hikers.” Of course, the opposite is true, too: “There are plenty of people who state that marijuana makes them feel tired or lazy, and thus, makes workouts more difficult.”

We asked the experts how a marijuana habit could impact an average workout session. Their thoughts, below:

(1) A high could tune you into your body.

The cognitive effects of cannabis include lower anxiety, changes in how you estimate time passing, and shifts in focus (you “tune into” your body or focus instead on your surroundings), says Gillman. When it comes to exercising high, researchers tend to extrapolate: “We can speculate based on what we do know about how marijuana impacts people psychologically in non-exercise contexts.” And a large part of exercise performance is psychological, says Gillman. So, she notes, it’s fair to assume that feeling a little less stressed, a little more focused, and like time is flying by could all help with performance.

(2) Cannabinoids might boost motivation.

It’s often believed that the runner’s high is caused by endorphins. But scientists have more recently discovered that that ‘feel-good’ feeling from movement also comes from your body’s version of cannabinoids (which are in pot), called endocannabinoids. Since these receptors in your brain interact with the brain’s reward pathways, exercise becomes rewarding, many researchers agree.

To this extent, it’s possible that cannabinoids (like those in marijuana) may have beneficial effects on exercise motivation, says Gillman. But it’s too soon to suggest toking as a technique for never missing a workout: Cannabis could also interfere with your body’s endocannabinoids, making you less likely to make that a.m. run, says Gillman.

(3) Buzzkill: Smoke will (still) hurt.

“We know that smoke can be detrimental to performance,” says Gillman. That could be why athletes who do use may be more likely to turn to a vaporizer or choose edibles, she notes. It makes sense: One study in The Harm Reduction Journal found that those who vaporize instead of smoking report fewer respiratory symptoms.

(4) Pot could help your DOMS.

In the states where medical marijuana is legal, one of the intended conditions is pain. And to this extent, it’s certainly possible pot could be a part of a healthy cool down, says Gillman. That’s because there is a good amount of research that shows cannabis can reduce pain, inflammation, and muscle spasms in humans. If you’re going to try it, look for a potent pain-relieving cannabinoid called cannabidiol (CBD), says Gillman. “It’s possible that anti-inflammatory properties of some forms of cannabis could help with sore muscles.” CBD is truly therapeutic: It’s non-psychoactive, so it won’t make you high.

To view full article by Cassie Shortsleeve, please visit: http://furthermore.equinox.com/articles/2016/04/exercise-and-marijuana?emmcid=emm-newsletter&utm_source=newsletter&utm_medium=email-member&utm_campaign=0420&cid=-Furthermore0420_B4202016

In the fitness industry, everyone’s obsessed with “more”. More cardio. More squats. More gym time. More calorie restriction. But if you’re not careful, “more” can lead to overtraining, injury, and illness. Here’s how to know what’s TOO MUCH when it comes to exercise.

I’ve been coaching clients for nearly 25 years and I’ve seen many of them treat their bodies like teenagers learning to drive a car.

Vroom.

Full speed ahead on killer workouts! Max effort each time! Add another hour of cardio!

Errrt!

Get hurt. Get sick. Feel discouraged.

Vroom.

Cut calories! Weigh and measure everything!

Errrt!

Lose control. Feel even more discouraged.

We see this cycle of alternatively slamming the gas, then brake, then gas, then brake with our Precision Nutrition Coaching clients.

When they decide to get moving, they go hard.

They throw everything — energy, time, resources — at their their weight loss, strength gain, or health goals. They feel invigorated and energized, high on their new workout drug.

Have you tried Workout X? they ask their coworkers.

Feel my quads, it’s amazing!

This full throttle approach seems to work for a little while.

Until… it doesn’t.

One day it’s hard to get out of bed. Shoulders and knees ache a bit. They get a bit of a cough or feel run down.

A week later they miss an easy lift. They reach for the ice pack. No big deal.

The week after, they’re dialing their chiro or physio’s office. Or lying on the couch with a back spasm that feels like giving bellybutton birth to a sea urchin.

What happened? Where did it all go wrong?

The problem isn’t the exercise, or even the intensity.

The problem is not balancing stress with recovery.

Exercise is a stressor. Usually a good one. But a stressor nonetheless.

If you exercise intensely and/or often, you add stress to a body that may already be stressed from other life stuff like work, relationships, travel, late nights, etc.

This isn’t a bad thing. Exercise can indeed help relieve stress.

But in terms of a physical demand, we still need to help our bodies recover from all the stress we experience.

How well you’ll recover (and how much extra recovery you might need) depends on your allostatic load — i.e. how much total stress you’re under at any given moment.

In other words, those days when you were late for work and your boss yelled at you and you spilled ketchup on your favorite shirt and you were up all night caring for a sick child — and then you went to the gym and tried to nail a PR?

It’ll take longer for you to recover from that workout than it would have if you’d done it on a day you slept well, woke up to sunshine, and had a terrific breakfast.

The right amount of exercise, at the right intensity, and the right time:

We train. We learn. We get healthier and stronger.

Too much exercise, with too high an intensity, too often:

We strain. We stress. We shut down. And break down.

Overtraining isn’t a failure of willpower or the fate of weak-minded wimps. Our bodies have complex feedback loops and elegant shutdown systems that actively prevent us from over-reaching or pushing ourselves too hard.

Two systems are at play:

Training too frequently and intensely — again, without prioritizing recovery — means that stress never subsides.

We never get a chance to put gas in the tank or change the oil. We just drive and drive and drive, mashing the pedals harder and harder.

If we “lift the hood” we might see:

As a result, you might experience:

Here’s the thing.

You don’t get to decide if you need recovery or not.

Your body will decide for you.

If you don’t build recovery into your plan, your body will eventually force it.

The more extreme your overtraining, the more you’ll “pay” via illness, injury, or exhaustion. The more severe the payback, the more “time off” you’ll need from exercise.

That’s a bummer. Now your car has stalled, or worse — gone backwards. Argh.

Some folks in our Precision Nutrition Coaching program worry that the prescribed workouts and daily habits won’t be enough. So they add more exercise and subtract food.

What’s driving them?

They might tell themselves it’s “for their health” or “to get the perfect body”.

But, the truth is, many people depend on their extreme exercise regimen to feel good about themselves.

Take this client story from Precision Nutrition Coach Krista Schaus:

Early on in the program, a client’s weight went up a few pounds on a particular measurement day. I went on high alert.

I called her and could hear the treadmill rolling in the background. “Uh, what are you doing… right now?”

Turns out she was into her 40th minute of a 60 minute “post-measurement day guilt workout”.

I yelled, “Get off the *&%! treadmill… Now!”

Right then and there we made each other a promise: No more extra work. PN training program only.

She was terrified of eating more and doing less. But, after her first week of “eating more and doing less”, she lost 3 pounds.

(Before, she had been doing “everything right” and not losing a pound.)

A few months later, she’d lost 10 pounds and 6% body fat. She looked healthy, fit and amazing. People would ask for her secret.

Those intense, laborious workouts can feel good. Almost… too good.

Strenuous exercise releases chemicals that kill pain and make us happy… temporarily.

By the way, these chemicals are also released when your body thinks you’re in big trouble and about to die. Their evolutionary job is to help us float away in a happy painless haze as the saber-toothed tiger is eating our arm off. So in a sense, they’re stress-related chemicals.

For some people, these chemicals become a “hit”.

Pushing their bodies to the limit and working hard becomes their drug.

It’s drilled into people’s heads via popular media: If you want control over how your body looks, hit the gym (and then hit it again).

Here’s another client’s story, in their own words:

I ran 7 marathons over the course of about 10 years, each time hoping that this training round would be the one that got me thinner.

But the harder I worked, the more frustrated I got. Which I used to propel myself harder, over more miles.

The more I trained, the hungrier I was. It was a massive battle against appetite, all day long.

I never got thinner. Sometimes I gained.

I got stressed out, cold after cold after random infection, and increasingly unhappy with myself.

For me, what I needed to finally drop those last 5-10 pounds wasn’t exercise for 1-2 hours a day, it was to go harder for shorter periods of time, and give myself enough downtime to recover.

It became so much easier to achieve a slight energy deficit when my body felt more at-ease, less pushed to the limits all the time.

Muscles stayed and got stronger. Fat shrunk away.

People who overtrain often want to try hard and do their best to reach their goals. They think they’re “doing what it takes”.

If some exercise is good, more must be better, right?

Precision Nutrition clients who are overtraining are often shocked to learn they’re doing too much. Nobody’s ever told them that there’s a “sweet spot” for exercise that balances work and recovery.

Usually, people learn about the risks of overtraining the hard way — like this client from our men’s coaching program:

Last week I injured my ribs and back. Not enough to put me out of commission, and it’s not serious, but it was a real pain in the a$s.

Certain positions and actions (like sneezing) felt like a knife in my side. I had to cut certain exercises out (e.g. push-ups), and I couldn’t jump rope or sprint, either.

I still did the workouts every day, but I had to cut back on the weight (I used about 80% of what I typically use), and for the intervals, scale back the intensity.

Now here’s the interesting part: When I was done with the workouts, I felt really good, as opposed to the fall-on-the-floor wiped out feeling I usually have. And I wasn’t sore the next day either.

In fact, I’ve been really looking forward to these workouts.

I thought: Hey, this is fun!

But then I had this other nagging thought: Am I just a wimp?

Anyway, all this got me thinking: What the hell am I working out so hard every day for? Should I be killing myself?

I’m not a competitor. Nobody knows or cares how fast I run or how much I squat.

I’m starting to think I should be ending a workout feeling like “I could do that again right now if I had to.” I call that “training”.

The opposite would be pushing myself to the limit frequently, feeling completely pooped after a workout. I call that “straining”.

It seems pretty obvious I won’t make a lot of fast progress by “training”, but on the other hand, I gotta wonder: How long can I keep going if I am “straining”?

Notice that this concept of training vs. straining is a true revelation to him!

Sometimes, less is more.

Putting in a consistent good effort over the long haul is much more sustainable than cycles of “crash and burn”.

This client’s slow and steady efforts paid off — he lost 20 pounds and 10 percent of his body fat in 6 months.

More importantly, he recovered, stayed uninjured, and kept having fun.

Look, if “pump till you puke” and hours of treadmill torture worked, we’d make our clients do it.

But it doesn’t work.

So we don’t do it.

Exercise should make us feel, look, perform and live better… not crush us.

Movement should help us function freely… not incapacitate us.

What if you could leave the gym feeling energized, not exhausted?

What if, instead of doing more, you could do better?

Here’s your first tip: “Overtraining” isn’t exactly the problem.

The problem is more like “under-recovering”.

Your body can actually handle a tremendous amount of work… if you recover properly and fully from that work.

Your stress-recovery pattern should look like rolling hills: For every up (training or life stress) there’s a down (recovery).

For every intense workout, there’s an equally intense focus on activities that help your body repair and rebuild.

This doesn’t mean you need to retreat to your dark and quiet blanket fort and get massages every day… although that does sound awesome.

Check out our recovery tips below.

When you factor in recovery as a crucial part of your training regimen, a funny thing happens.

You start to think of training completely differently.

What if you could “exercise” on a continuum — where every movement “counts”?

What if you could balance high with low, heavy with light, work with play in a natural, organic rhythm?

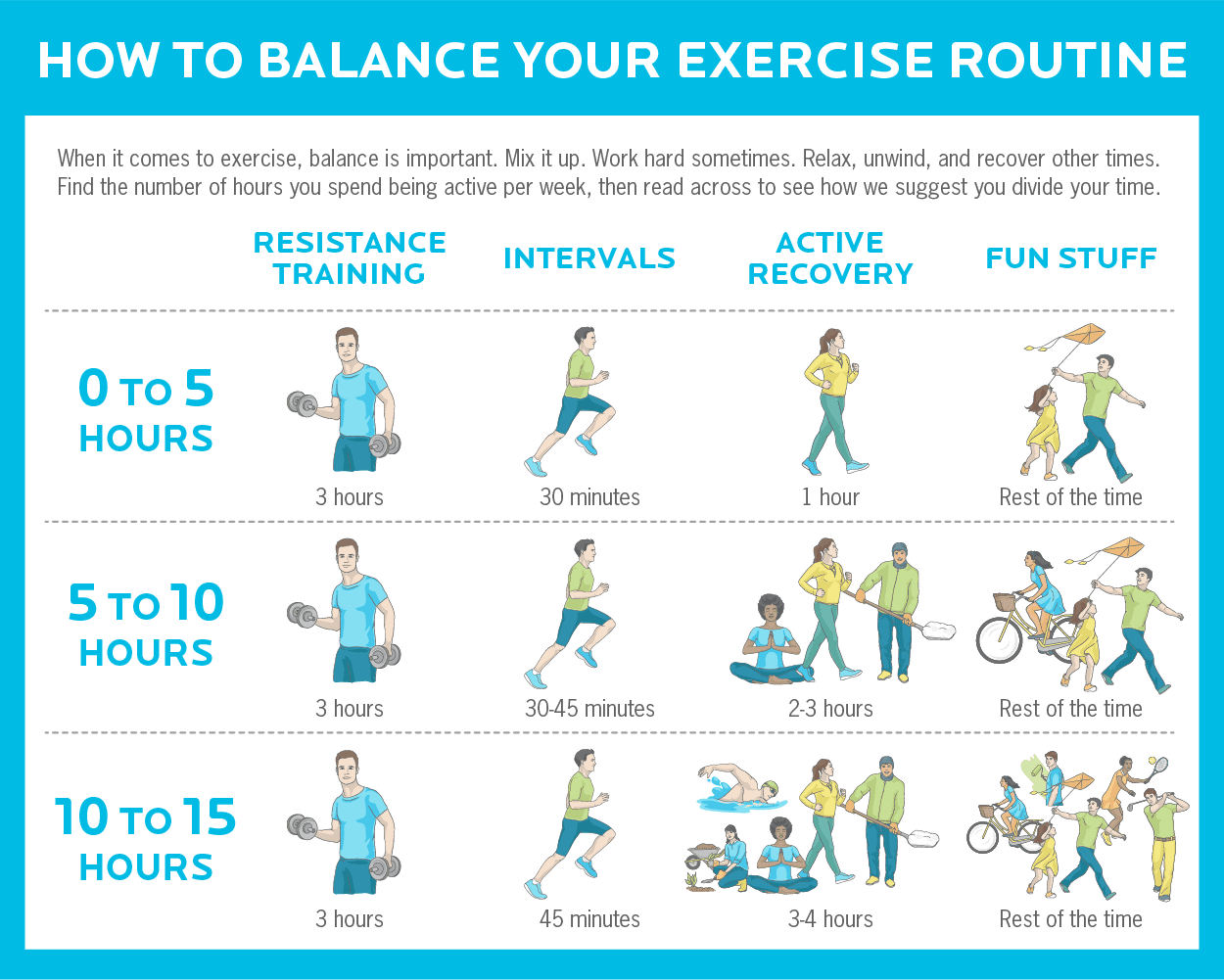

An effective physical activity routine incorporates:

You can do that no matter how much time you have to devote to physical activity.

Here’s what the balance looks like in Precision Nutrition Coaching:

Precision Nutrition Coaching clients who have the most success aren’t usually the ones who do the biggest, most challenging workouts.

Instead, they’re the ones who find small ways of getting movement whenever and wherever they can.

That includes real-life functional movement, such as:

When you think of movement this way, it stops becoming “a workout” (i.e. a chore, or a gauntlet you have to psych yourself up for) and starts becoming “your daily life” (i.e. something that is easy, seamless, and always with you).

If you’re feeling some of the symptoms described in this article, here are a few steps you can take to start feeling better.

For some of us, skipping a workout is no biggie.

For others, taking a day off requires effort. Doing less can make you feel uneasy.

If spending more time away from your self-imposed bootcamp freaks you out, ask yourself:

If you’re beating yourself up and not getting anywhere, maybe it’s time to take a different approach.

What’s really going on under the hood?

Do a mind-body scan: Lie quietly for a few minutes and bring your focus slowly from your feet to your head. What do you feel?

Practice becoming more aware of your body cues.

What does your body feel like when it’s well-rested? How do you know when it needs a break?

If you’re feeling:

…consider changing up your workout routine.

Recovery won’t happen by accident. Plan it, prepare for it and hunt it down.

Schedule that massage. Tell your friends to save the date for the citywide scavenger hunt. And block off Sunday afternoon for guilt-free goof-off time.

Whatever you do, remember that your recovery — what you do between workouts — is just as important as training.

Some ideas:

There’s time for tough workouts and time for taking it easy. There’s time for long runs, and there’s time for throwing a frisbee around.

Doing the same thing over and over again isn’t doing your body any good. Mix up your exercises, and the intensity.

If you’re not sure how much of each you’re getting, try keeping a workout journal for a week or two.

What could you use a little more of?

Where could you ease back?

Find some new ways to get active without being in the gym.

Incorporate some silly, goofy play time into your routine. See how it feels.

And there’s a reason why kids naturally run, jump, roll, and wiggle their bodies around: Fun is a huge part of how we learn to move and interact in the world. Continuing this process keeps us healthy and young.

Laughing activates the recovery system, as does even just smiling. Lighten up and loosen your white-knuckle grip on life, Sergeant Hardcore.

Here are some ideas for good old-fashioned fun:

The only message you’ve likely ever gotten about staying fit is: put the pedal to the metal. Now it turns out you’re actually in overdrive?

If you’re feeling frustrated or confused (or exhausted or stressed) — team up with someone.

Find an active friend, an interested spouse, a parent you want to spend more time with, or a local trainer/coach/sensei. Together, experiment with a fun, balanced approach to your physical activity.

Your “car” will thank you.

For full article by John Berardi please visit: http://www.precisionnutrition.com/are-you-overtraining

We teamed up with MR PORTER on a series of short films showcasing the principles everyone must master to create a body that looks—and is—truly fit. First up: How to Build Strength. Next: How to Be Flexible.

Powerful is probably not the first word you would use to describe flexibility. There’s such an inherent softness and passiveness to it. But it was the power that first drew Equinox yoga instructor Johan Montijano away from his more vigorous pastimes of biking and surfing towards stretching and flexibility.

“I was a typical guy. Muscling everything. And always wanting to be in control,” says Montijano. “I didn’t realize that could translate into something like yoga, but it can.”

Though skeptical going in, halfway through his first class something clicked. He started to breathe and relax into the poses. “I realized I was healing my own body. I was in control. Using my breath, I was able to direct the healing exactly where I needed it most,” he says. “It was extremely empowering.”

And the magic is not just limited to the yoga studio. Taking just a few minutes each day to breathe and stretch can have an incredible impact on the body. Watch the video above as Montijano takes you through some of his favorite stretches and poses that target key areas of tightness in the body.

Namaste.

For full article by Liz Miersch please visit http://furthermore.equinox.com/articles/2015/05/fit-for-fit-flexibility?emmcid=emm-newsletter&utm_source=newsletter&utm_medium=email-member&utm_campaign=0509&cid=-Furthermore_0509A592016