Everybody gets sick. But it’s tough to know what to do about it. Should you “sweat it out” in the gym? Or get some rest instead? In this article we clear up the confusion. So that next time you come down with the flu or a cold, you’ll know what to do.

Your friendly neighborhood gym. You’re warmed up and ready for a great workout. Then, all the sudden, Mr. Sneezy walks by. Coughing, sniffling, and heavy mouth-breathing. He’s spraying all over the benches and mats.

“Dude, shouldn’t you just stay home and rest?” you’re thinking. (And, while you’re at it, stop sharing those nasty germs?)

But maybe Mr. Sneezy’s onto something. Maybe he’ll be able to sweat the sickness out of his system, boosting his immune system along the way.

What’s the right approach? Let’s explore.

The immune system: A quick and dirty intro

Every single day, bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites come at us. Folks, it’s a germ jungle out there!

The most common invaders are upper respiratory tract invaders, or URTI’s. Yep, I’m talking about

- colds,

- coughs,

- influenza,

- sinusitis,

- tonsillitis,

- throat infections, and

- middle ear infections.

Luckily, our immune system has got a plan. When faced with foreign attack, it works hard to defend us. Without the immune system, we’d never have a healthy day in our lives.

Our immune cells originate in our bone marrow and thymus. They interact with invaders through the lymph nodes, the spleen, and mucus membranes.

This means they first make contact in your mouth, gut, lungs, and urinary tract.

The innate and adaptive immune response

Our innate (natural) immune system is our non-specific first line of defense.

It includes:

- physical/structural barriers (like the mucous lining in nasal passages),

- chemical barriers (like our stomach acids), and

- protective cells (like our natural killer ‘NK’ cells, white blood cells that can destroy harmful invaders).

This immune system develops when we’re young.

Interestingly, women tend to have a stronger overall innate immune response. (Maybe this is why they often do better than men when it comes to colds. But they suffer more often from autoimmune diseases.)

Then there’s the adaptive (acquired) immune system.

This is a more sophisticated system composed of highly specialized cells and processes. It kicks in when the innate immune system is overcome.

The adaptive immune system helps us fight infections by preventing pathogens from colonizing and by destroying microorganisms like viruses and bacteria.

Cue the T and B cells. These specialized white blood cells mature in the thymus and bone marrow, respectively. And believe it or not, they actually have a kind of memory.

It’s this memory that makes them so effective. Once they “recognize” a specific pathogen, they mobilize more effectively to fight it.

This is what we mean when we talk about “building immunity.”

Ever wondered why kids get sick with viruses more often than adults? It’s because they haven’t had as much exposure so their adaptive immune systems are less mature.

What’s more, the acquired immune response is the basis for vaccination. Subject your body to a tiny dose of a pathogen, and it will know what to do when confronted with a bigger dose.

Genius!

Should you exercise while sick?

Let’s get one thing clear from the start: there’s a difference between “working out” and “physically moving the body.”

A structured workout routine — one where you’re breathing heavily, sweating, working hard, and feeling some discomfort — awakens a stress response in the body.

When we’re healthy, our bodies can easily adapt to that stress. Over time, this progressive adaptation is precisely what makes us fitter and stronger.

But when we’re sick, the stress of a tough workout can be more than our immune systems can handle.

Still, there’s no reason to dive for the couch the minute you feel the sniffles coming on. Unless you’re severely out of shape, non-strenuous movement shouldn’t hurt you — and it might even help.

What do I mean by “non-strenuous movement”? Well, it might include: walking (preferably outdoors), low intensity bike riding (again, outdoors), gardening, practicing T’ai Chi.

In fact, all of these activities have been shown to boost immunity.

They aren’t intense enough to create serious immune-compromising stress on the body. Instead, they often help you feel better and recover faster while feeling under the weather.

That’s why Dr. Berardi often recommends low intensity non-panting “cardio” when suffering from colds. Done with minimal heart rate elevation, preferably outside, these activities seem to offer benefits.

What about “working out”?

Non-strenuous movement and purposefully working out are different.

Plus, as you probably know, not all workouts are created equal. There are low intensity workouts and high intensity workouts — and all sorts of workouts in between.

But what’s low to one person might be high to another. So how can you decide what level of intensity counts as strenuous?

Let your own perceived level of exertion be your guide.

In general, a low to moderate intensity workout will leave you feeling energized. A high intensity workout, on the other hand, delivers an ass-kicking.

If you’re sick, it makes sense to avoid the ass-kicking.

Let’s take a look at why.

How exercise affects the immune system

Exercise may play a role in both our innate and our adaptive immune response.

Here’s how:

- After one prolonged vigorous exercise session we’re more susceptible to infection. For example, running a marathon may temporarily depress the adaptive immune system for up to 72 hours. This is why so many endurance athletes get sick right after races.

- However, one brief vigorous exercise session doesn’t cause the same immune-suppressing effect. Further, just one moderate intensity exercise session can actually boost immunity in healthy folks.

- Interestingly, chronic resistance training seems to stimulate innate (but not adaptive) immunity. While chronic moderate exercise seems to strengthen the adaptive immune system.

In the end, here’s the pattern:

- Consistent, moderate exercise and resistance training can strengthen the immune system over time. So, by all means, train hard while you’re healthy.

- But single high intensity or long duration exercise sessions can interfere with immune function. So take it easy when you’re feeling sick.

Exercise, stress, and immune function

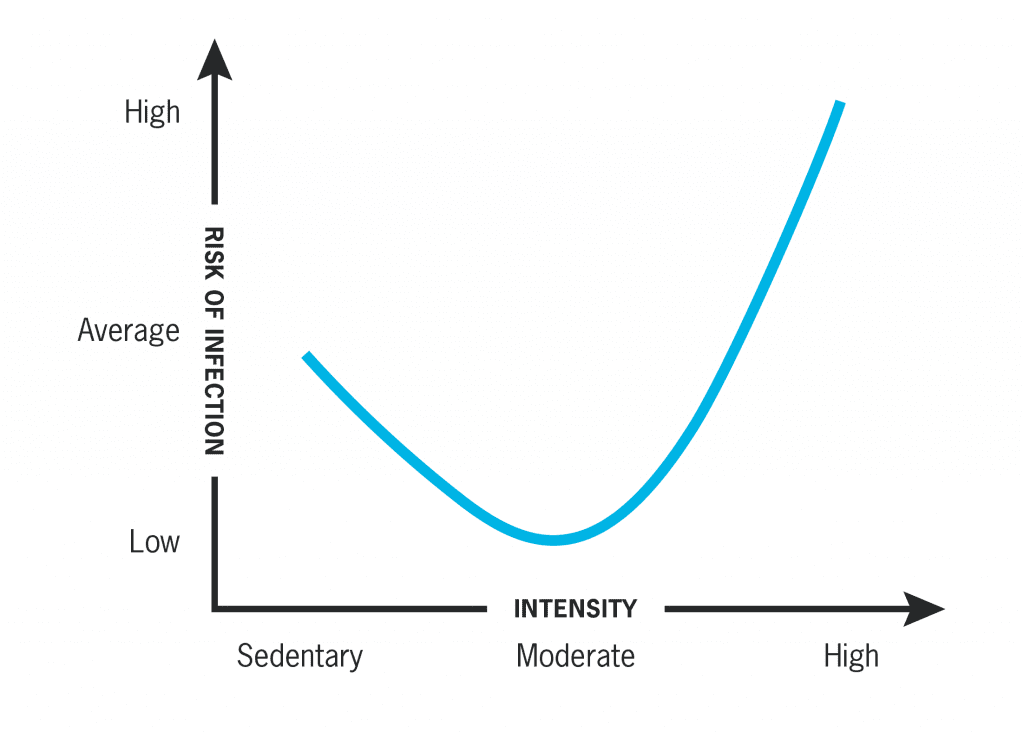

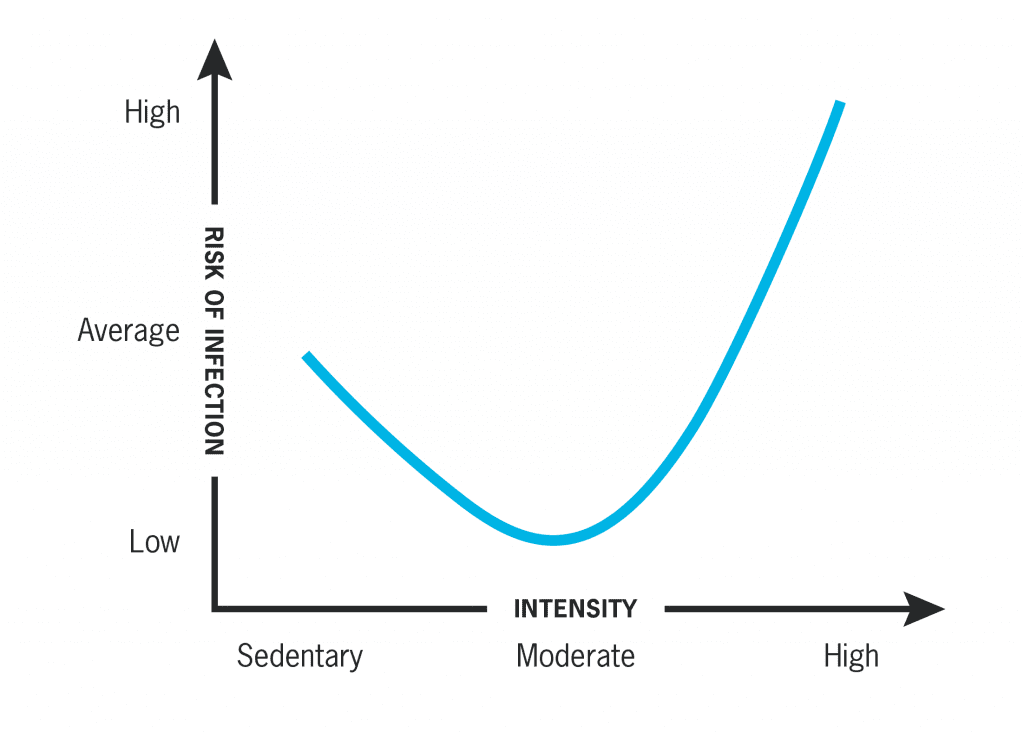

A group of scientists gathering data on exercise habits and influenza found:

- People who never exercised got sick pretty often.

- People who exercised between once a month and three times a week did the best.

- People who exercised more than four times a week got sick most often.

Enter the J-shaped curve theory.

In simple terms, being sedentary or exercising too much can lower immunity, while something in the middle can improve immunity.

The role of stress

Exercise isn’t the only factor that affects the immune system. Stress plays a big role too.

Let’s take a look at the different stressors a person might face on any given day.

- Physical stress: exercise, sports, physical labor, infection, etc.

- Psychological stress: relationships, career, financial, etc.

- Environmental stress: hot, cold, dark, light, pollution, altitude, etc.

- Lifestyle stress: drugs, diet, hygiene, etc.

Stress triggers an entire cascade of hormonal shifts that can result in chronic immune changes.

- Acute stress (minutes to hours) can be beneficial to immune health.

- Chronic stress (days to years) can be a big problem.

So, if you’re angry, worried, or scared each day for weeks, months, or even years at a time, your immunity is being compromised. And you’re more likely to get sick.

Sickness and stress

It’s pretty obvious that if you’re actually sick and fighting an infection, your immune system will already be stressed.

And if you add the stress of prolonged vigorous exercise, you might, quite simply, overload yourself. That will make you sicker.

Plus, your history of infections can influence how the immune system responds during exercise. This can include everything from the common herpes simplex virus, varicella zoster, and cytomegalovirus, to hepatitis and HIV.

A healthy body might adapt to all that. But a body that’s fighting an infection is not a healthy body.

Overtraining and infection

What’s more, sudden increases in exercise volume and/or intensity may also create new stress, potentially allowing a new virus or bacteria to take hold, again kicking off a sickness.

Consider the 1987 Los Angeles Marathon, where one out of seven marathon runners who ran became sick within a week following the race. And those training more than 60 miles per week before the race doubled their odds for sickness compared to those training less than 20 miles per week.

This seems to work the opposite way as well. Chronic infections may actually be a sign of overtraining.

Learning from cancer & HIV

Exercise therapy is often recommended for patients with cancer in part because of how it modulates the immune system. Exercise seems to increase NK cell activity and lymphocyte proliferation. In other words, it looks like exercise can be helpful.

Exercise interventions in those with HIV seem to help prevent muscle wasting, enhance cardiovascular health, and improve mood. We’re not sure how this works, though it may help to increase CD4+ cells.

Other factors affecting immunity

Besides stress, there are a host of other factors that can affect our immunity, and these can interact with exercise, either offering greater protection or making us more likely to get sick.

We’ve already touched on some of these. Here are a few more.

Age

Our innate immune response can break down as we get older. But here’s the good news: staying physically active and eating a nutritious diet can offset many of these changes.

Gender

Menstrual phase and oral contraceptive use may influence how the immune system responds to exercise. Estrogens generally enhance immunity while androgens can suppress it. (Again, this may explain why women tend to do better with colds than men.)

Sleep

Poor quality sleep and/or prolonged sleep deprivation jeopardizes immune function.

Climate

Exercising in a hot or cold environment doesn’t appear to be that much more stressful than exercising in a climate controlled environment.

For example, exercising in a slightly cool environment might boost the immune system. But full-fledged hypothermia may suppress immune function. While using a sauna or hot bath may stimulate better immunity in those with compromised immune function.

Altitude

Exposure to higher altitudes has a limited influence on immunity.

Obesity

It’s unclear exactly how obese folks respond to exercise in terms of immunity. Changes in insulin sensitivity and inflammation at rest may blunt or exaggerate their immune response to exercise.

Mood

There’s evidence that immune alterations affect mood and inflammation. Clinical depression is two to threefold higher among patients with diseases that have elevated inflammatory activity.

(Note: moderate exercise appears to act as an anti-inflammatory in those with inflammatory conditions).

IL-6

There is a theory that IL-6 (a compound released after prolonged intensive exercise) may be produced in abnormal ways in some people, leading to fatigue, flu-like symptoms, and depressed mood.

Training age

The more “trained” you are, the better your body tends to handle exercise. In other words, it’s not as much of a stressor.

Just in case you glossed over the previous sentence I’ll reiterate it: a higher level of fitness is protective as it may limit the stress response to exercise.

Textbook guidelines for exercising while sick

- Day 1 of illness:

Only low intensity exercise with symptoms like sore throat, coughing, runny nose, congested nose.

No exercise at all when experiencing muscle/joint pain, headache, fever, malaise, diarrhea, vomiting.

- Day 2 of illness:

If body temp >37.5-38 C, or increased coughing, diarrhea, vomiting, do not exercise.

If no fever or malaise and no worsening of “above the neck” symptoms: light exercise (pulse <120 bpm) for 30-45 minutes, by yourself, indoors if winter.

- Day 3 of illness:

If fever and symptoms still present: consult doctor.

If no fever/malaise, and no worsening of initial symptoms: moderate exercise (pulse <150 bpm) for 45-60 min, by yourself, indoors.

- Day 4 of illness:

If no symptom relief, no exercise. Go to doctor.

If fever and other symptoms improved, wait 24 hours, then return to exercise.

If new symptoms appear, go to doctor.

Note: Some illnesses can indicate serious infections. So if you aren’t feeling better and recovering, see your doctor.

Also note: Ease back into exercise in proportion to the length of your sickness. If you were sick for 3 days. Take 3 days to ease back in.

To exercise or not? What the pros recommend

Now you know something about the immune system and how exercise interacts with it. But you still might be wondering whether you should exercise when you’re sick. I asked some of the best in the business for their insights.

The consensus: Let your symptoms be your guide and use common sense. And remember the distinction between exercise and working out.

INSIGHT

1 |

Nick TumminelloI follow the general guideline that if it’s above the neck, it’s okay to train, and do so at an intense level. Just wash your hands before you touch all of the equipment to minimize giving your head cold to others at the facility. Anything below the neck, don’t come into the gym, and take it easy until you’re on the back end of it. |

INSIGHT

2 |

Alwyn CosgroveBasically we don’t like people to train when they are ill. I can’t see any upside to doing so. |

INSIGHT

3 |

Dr. Bryan WalshLet your symptoms be your guide. If you’re up for a walk or some light cardio, go for it. If you want to do some lighter weight, higher rep stuff just to keep things moving, that’s probably okay, too. But if you want to sit around watching re-runs of Married With Children, laughter is great medicine as well. |

INSIGHT

4 |

Dean SomersetTypically I ask clients to stay out of the gym if they have a cold. For one, their own workouts may not be very productive especially if they have respiratory congestion or irritation, and second because I don’t want to catch it! The gym typically isn’t the cleanest place in the world, so a cold bug could be easily spread around through the population by handling equipment or through respiratory droplets in the air. |

INSIGHT

5 |

Dr. Spencer NadolskyWith a viral URTI, I have no problem with my patients doing some light exercise. Anecdotally, sometimes it makes them feel better. There’s data to show those who exercise actually get less URTIs. If it’s a little more severe such as influenza (or something similar), I generally keep them focused on hydration and tell them to skip the workout. If they have any history of asthma, I am careful to make sure they have their rescue inhaler if they do feel up to exercising. |

INSIGHT

6 |

Dr. Christopher MohrIn terms of exercise, I let them “decide” what’s best for them depending on how they feel. If you can’t stop coughing or your head feels like it’s about to explode, I’d suggest taking some down time and getting plenty of sleep, including naps if possible. For me, I’ve found a short walk is still significantly better than nothing — and trying to get outside to do that vs. being stuck on a treadmill walking in circles. Trying to move iron in the gym is a bit much. |

INSIGHT

7 |

Eric CresseyI generally ask them just how bad it is on a scale of 0 to 10. Zero would be feeling absolutely fine, whereas a 10 would be the worst they’ve ever felt (e.g., violently ill and on their death bed). If it’s anything under a 3 (say, seasonal allergies), I’m fine with them training — albeit at a lower volume and intensity. We might even just do some mobility work or something to that effect.I think the important separating factor is that we’re looking for the difference between just not feeling 100% (allergies, stress, headache) and actually being sick and contagious, which we absolutely don’t want in the gym — for the sake of that individual and those who are training around him/her.

Of course, this is pretty subjective — but what I think it does help us to do is avoid skipping days that would have been productive training days. Everyone has had those sessions when they showed up feeling terrible, but after the warm-up, they felt awesome and went on to have great training sessions. We don’t want to sit home and miss out on those opportunities, but we also don’t want to get sicker or make anyone else sicker — so it’s a definite balancing act.

|

INSIGHT

8 |

Dr. John BerardiUnless you’re feeling like a train wreck I always recommend low intensity, low heart rate “cardio” during the first few days of sickness. Generally I prefer 20-30 minute walks done either outside (in the sunshine) or on a home treadmill (if you can’t get outside).If you keep the intensity low and the heart rate down you’ll end up feeling better during the activity. And you’ll likely stimulate your immune system and speed up your recovery too. But even if you don’t speed up your recovery, you’ll feel better for having moved.

|

Exercise activity cheat sheet

Activities to consider when you’re sick.

- Walking

- Jogging

- Swimming

- Biking

- Qi gong

- T’ai Chi

- Yoga

All of these would be done at a low intensity, keeping your heart rate low. They’d also preferably be done outdoors in mild temperatures. Inside is fine, though, if you can’t get outside.

Activities to avoid when you’re sick.

- Heavy strength training

- Endurance training

- High intensity interval training

- Sprinting or power activities

- Team sports

- Exercise in extreme temperatures

And, for the sake of the rest of us, stay out of the gym. At the gym, you’re much more likely to spread your germs to others. Viruses spread by contact and breathing the air near sick people.

So, if you feel up to physical activity, again: do it outside or at your home gym.

We all thank you.

What you should do

If you feel healthy and simply want to prevent getting sick:

- Stay moderately active most days of the week.

- If you participate in high-intensity workouts, make sure you’re getting enough rest and recovery time.

- Manage extreme variations in stress levels, get plenty of sleep, and wash your hands.

If you are already feeling sick, let symptoms be your guide.

- Consider all the stress you’re managing in your life (e.g., psychological, environmental, and so forth).

- With a cold/sore throat (no fever or body aches/pains), easy exercise is likely fine as tolerated. You probably don’t want to do anything vigorous, no matter how long in duration.

- If you have a systemic illness with fever, elevated heart rate, fatigue, vomiting, diarrhea, muscle and joint pain/weakness, and enlarged lymph nodes, get some rest! If you have a serious virus and you exercise, it can cause problems.

By Ryan Andrews

For Ryan Andrews' full article, visit precisionnutrition.com and you can explore the references he uses as well

WHICH REST IS BEST?