To most people, healthy movement = exercise. As in cardio, crunches, and fitness models. But moving your body is about so much more, like improved thinking, stronger relationships, and expressing your purpose in life.

When most people hear healthy movement, they think exercise or fitness or looking better or weight loss.

Sometimes, vanity.

Often, fitting into social norms.

“The man” telling you what to do (or how to be).

Moral righteousness packaged as 6am Hot Detox Spin-Late Pump class or an entire weekend of Instagram-worthy self-punishment.

But healthy movement is actually more interesting, liberating, and, frankly, crucial than all that.

In my years as a health and fitness coach, here’s the most important thing I’ve discovered: Developing a body that moves well is the ticket to a place where you feel — finally — capable, confident, and free.

We are all, literally, born to move.

It’s no secret: Human life has become structured in a way that makes it very easy to avoid movement.

We sit in cars on the way to work. At work we sit at our desks for much of the day. Then we come home and sit down to relax.

That’s not what our bodies are built for, so creaky knees, stiff backs, and “I can’t keep up with my toddler!” have become the norm.

Sure, if you can’t move well, it may be a sign that you aren’t as healthy as you could be. But the quality and quantity of your daily movement — your strength and agility — are actually markers for something much more important.

In my line of work, you watch a lot of people lose a lot of weight. The results would shock you — and I’m not talking about how they look on the beach in their bathing suits (although there is always a big celebration for that).

Most often, the thing people are most excited about after they go from heavy and stiff to lean and agile is this feeling that they’re now living better. They notice they’re:

- more energetic and young-feeling,

- able to do things they’ve been putting off for years,

- empowered,

- proud of their lifestyle, and

- free from many of the anxieties and limitations that held them back for so long.

They’re happier, but not just because they wanted to look better, and now they do. They’re happier because their bodies now work like they’re supposed to. They can now do things they know they ought to be able to do.

As humans, we move our bodies to express our wants, needs, emotions, thoughts, and ideas. Ultimately, how well we move — and how much we move — determines how well we engage with the world and establish our larger purpose in life.

If you move well, you also think, feel, and live well.

It’s proven that healthy movement helps us:

- Feel well, physically and emotionally

- Function productively

- Think, learn, and remember

- Interact with the world

- Communicate and express ourselves

- Connect and build relationships with others

We don’t need “workouts” to move.

Shocking secret: There’s nothing magic about a resistance circuit, the bootcamp class at your gym, or the latest branded training method.

Our ancestors didn’t need to “work out” when they were walking, climbing, running, crawling, swimming, clambering, hauling, digging, squatting, throwing, and carrying things to survive. Nor did they need an “exercise class” when they ran to get places, danced to share stories or celebrate rituals, or simply… played.

“Working out” is just an artificial way to get us to do what our bodies have, for most of human history, known and loved — regular movements we lost and forgot as we matured as a species.

We may not hunt for dinner anymore, and we may opt for the elevator more often than not.

We may move less. But movement is still programmed into the human brain as a critical aspect of how we engage with the world.

Therefore, to not move is a loss much, much greater than your pant size.

What factors determine how your body moves?

While there are universal human movement patterns, our specific movement habits are unique to us, and to our individual bioengineering.

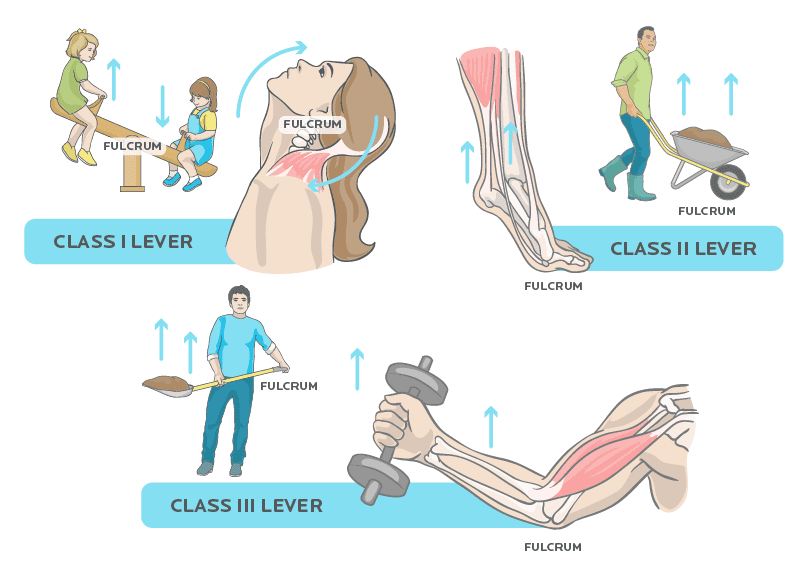

Basically, the human body amounts to a sophisticated pile of interconnected levers:

- Muscles are attached to bones with tendons.

- These tendons connect to two (or more) bones across a joint.

- When a muscle contracts, or shortens, the tendons pull on the bone.

- That contraction and pull causes the joint to flex (bend) or extend (straighten).

How you move is determined by the size, shape and position of all of those parts, along with anything that adds weight, like body fat.

If you’re a tall person with long bones it may be harder for you to bench press, squat, or deadlift the amount of weight your shorter buddy can, because your range of motion is much bigger than your friend’s, so you have to move that weight a longer distance with much longer levers.

(This is why there aren’t many super-tall weightlifters or powerlifters, and why great bench pressers usually have a big ribcage and stubby T-Rex arms.)

But you can probably spank your short friend at swimming, climbing, and running.

If you’re bottom-heavy and/or shorter, you may not be able to run as fast as your taller friend. But you may have exceptional balance.

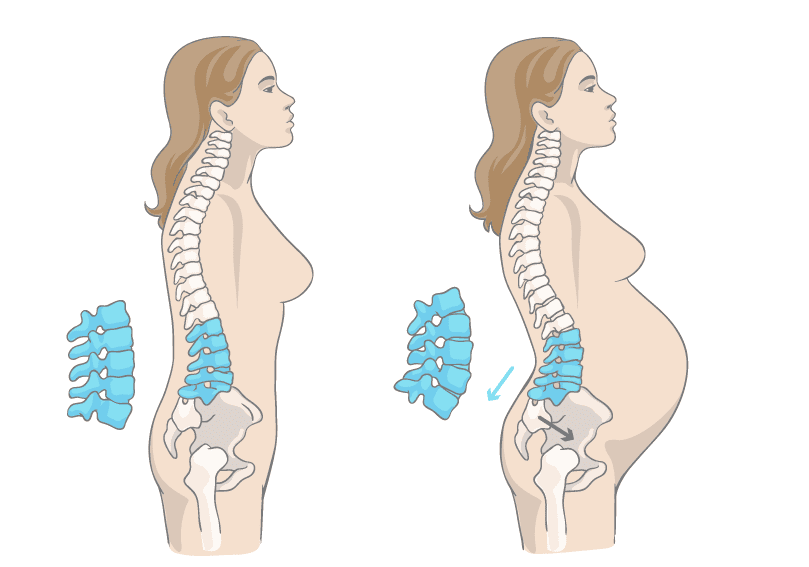

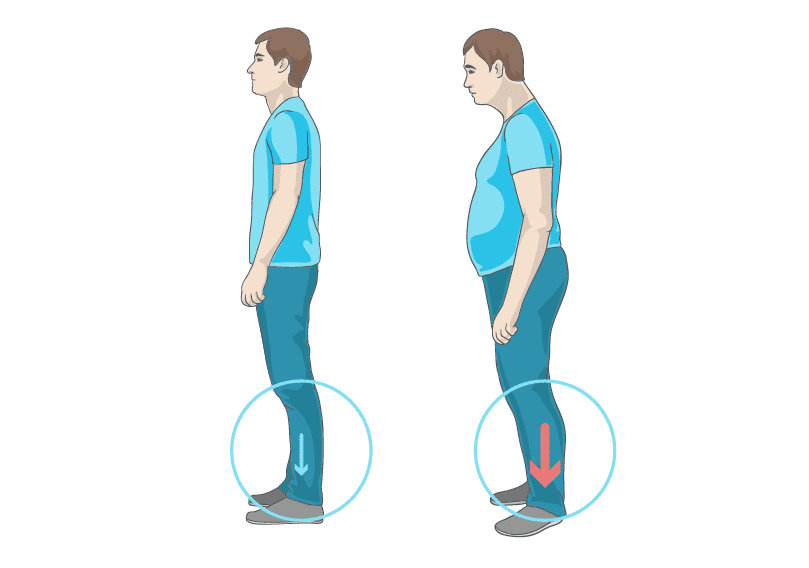

If you’ve gained weight in your middle (or if you’re pregnant), you may have back pain. That’s because the extra belly weight pulls downward on the lumbar spine (lower back).

When the lumbar spine is pulled down and forward (“lordosis”):

- The pelvis also tips forward (“anterior pelvic tilt”), which pokes the tailbone back and the belly forward — aka Donald Duck Butt.

- The upper/mid back may round to compensate (“kyphosis”).

The downward pull can also affect all the joints below (the pelvis, hip, knee, and ankle).

Conversely, it also works in the opposite direction, where, say, ankle stiffness can affect movement in the lower back.

If you have wider shoulders (“biacromial width”), then you have a longer lever arm, which means you can potentially throw, pull, swim or hit better.

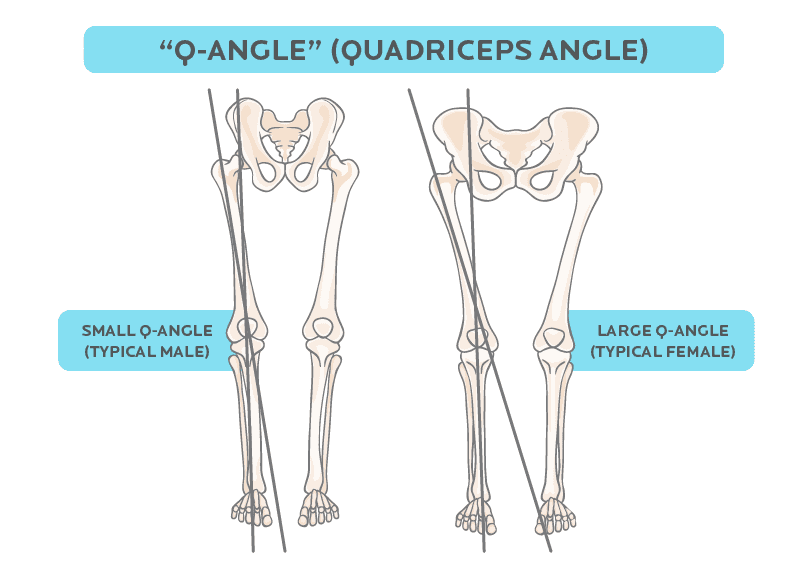

If you have longer legs, then you have longer stride, which means you can potentially run faster. This is especially true if you also have narrower hips, which create a more vertical femur angle (“Q-angle”), allowing you to waste less energy controlling pelvic rotation.

Some variations in movement, we are given by nature and evolution. Other variations, we learn and practice.

If you’re a woman who’s top-heavy, you may have developed a hunch in your thoracic spine (upper and mid-back), whether from the physical weight of your breasts or from the social awkwardness of being The Girl With Boobs in middle school.

Or, if you got really tall at an early age, you may have developed a habitual hunch to hide your size or communicate with hobbits like me.

Yet the structural engineering remains important. Especially if we understand how our structures and physical makeup affect our movements.

For instance:

Body fat and weight change how we move.

This is especially true if you don’t have enough muscle to drive the engine.

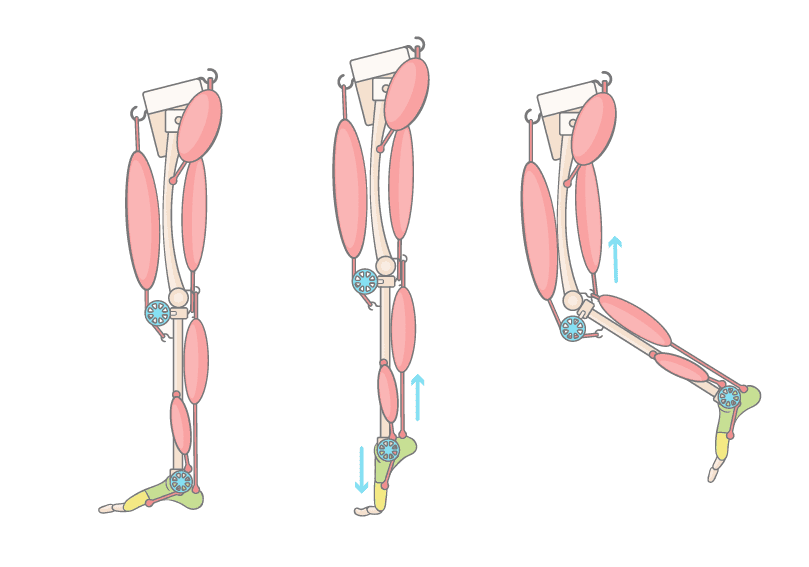

At a healthy weight, your center of mass is just in front of your ankle joints when you stand upright.

However, the more mass you have, especially if you have extra weight in front, the harder your lower legs and feet have to work to keep you from tipping forward.

This puts additional torque (rotational force) on ankle joints.

Once you start walking — which is, essentially, a controlled forward fall — you have to work even harder to compensate.

Any unstable or changing surface (stairs, ice, fluffy carpet, a wet floor), requires your lower joints to adjust powerfully and almost instantaneously — literally millisecond to millisecond.

As a result, obese children and adults fall more often.

Human bodies are amazingly adaptable and clever, but nevertheless, physics can be an unforgiving master.

The good news is that this is generally reversible.

No matter where you’re starting, the more you move, the better your body will function.

When we move:

- our muscles contract;

- we load our connective tissues and bones;

- we increase our respiration and circulation; and

- we release particular hormones and cell signals.

All of these (and a variety of other physiological processes) tell our bodies to use its raw materials and the food we eat in certain ways.

For instance, movement tells our bodies:

- to retrieve stored energy (e.g. fat or glucose) and use it;

- to store any extra energy in muscles, or use it for repair, rather than storing it as fat;

- to strengthen tissues such as muscles, tendons, ligaments, and bones; and

- to clear out accumulated waste products.

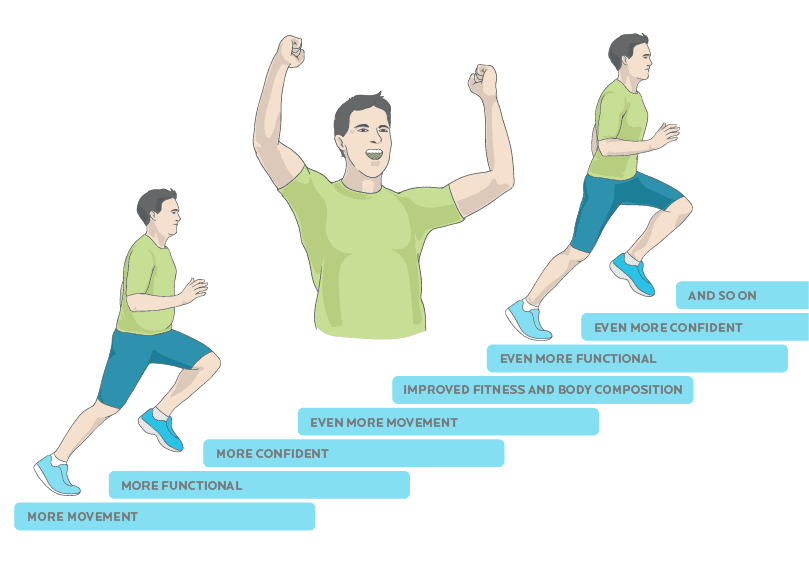

And improved body functions ensure you’ll be able to move well and:

- climb stairs or hills

- step over obstacles

- carry groceries

- stand up from sitting down, or get up from the floor

- grasp and hold objects like a hammer

- pull or drag things like a heavy door or garbage can

- walk an excitable dog

The more we can do confidently and capably, the fitter we’ll be. Even better, that means we’ll do more. That leads to more fitness. And this virtuous cycle continues.

Movement does more than just “get us into shape”.

Despite eyeglasses and iPhones, humans are still animals. We’re meant to move with the grace and agility of a tiger (or a monkey). And movement offers us a tremendous number of (sometimes surprising) benefits.

Movement is how humans (and other animals) interact with the world.

As babies, we immediately start grabbing things, putting things in our mouths, reaching for things, and clinging to our (now less furry) primate parents.

We are tactile, kinesthetic beings who must directly interact with physical stimuli: touching, tasting, manipulating, moving ourselves around objects in three-dimensional space.

Movement helps us connect and build relationships with others.

Movement is a sensor for the world around us.

In one study, when people’s facial muscles were paralyzed with Botox, they couldn’t read others’ emotions or describe their own. We need to mimic and mirror the body language and facial cues of one another to connect emotionally and mentally.

From the puffed-chest posturing of drunken young men outside a bar, to Beyonce’s fierce dance moves, to the mating rituals like close leaning and eye contact, to the laser stare your mom gives you when she knows you’re up to no good:

Movement gives us a rich, nuanced expressive language that goes far beyond words, helping us build more fulfilling and lasting relationships, with fewer misunderstandings, disconnections, or communication bloopers.

Movement helps us think, learn, and remember.

You might imagine that “thinking” lives only in your head.

But in reality, research shows we do what’s called “embodied cognition” — in which the body’s movements influence brain functions like processing information and decision making, and vice versa.

So “thinking” lives in our entire bodies.

But even if thinking were limited to our brains, there is evidence that movement and thought are intertwined.

It turns out that the cerebellum — a structure at the base of the brain previously thought to only be used for balance, posture, coordination, and motor skills — also plays a role in thinking and emotion.

Also, movement supports brain health and function in many ways, by helping new neurons grow and thrive (i.e. neurogenesis).

Every day, our brains produce thousands of new neurons, especially in our hippocampal region, an area involved in learning and memory. Movement — whether learning new physical skills or simply doing exercise that improves circulation — gives the new cells a purpose so that they stick around rather than dying.

Thus, movement:

- helps maintain existing brain structures,

- helps slow age-related mental decline,

- helps us recover if our brain is injured or inflamed,

- lowers oxidative stress, and

- increases the levels of a substance known as brain-derived neurotrophic factor, or BDNF, which is involved in learning and memory.

Move well, move often, get smarter.

Movement affects how we feel physically and emotionally.

People of all shapes and sizes say they have a better quality of life, with fewer physical limitations, when they are physically active.

If you exercise regularly, you probably know that kickass workouts can leave you feeling like a million bucks. (Personally I think of mine as anti-bitch meds.)

Research that compared exercise alone to diet alone found:

People who change their bodies with exercise (rather than dieting) feel better — about their bodies, about their capabilities, about their health, and about their overall quality of life — even if their weight ultimately doesn’t change.

(Now… just imagine if you combined the magic of exercise with brain-boosting and body-building nutrition!)

Find out what “healthy movement” looks like for you.

Not everyone has to be (or can be) a ballet dancer or Olympic gymnast. As a 5-foot, 40-something woman who can’t run well nor catch a ball, I’m fairly sure the NBA and NFL won’t be calling me.

But I’m also not saying that, “Well, guess I shouldn’t climb the stairs because of my Q-angle” is the way to go.

I’m saying: Today, pay special attention to how you move.

Be curious.

As you go through the mundane activities of your day, notice how your unique body shapes your movements.

How do you move… and how could you potentially move?

In our coaching programs, we work with a lot of clients who have physical limitations, such as:

- chronic pain or movement restrictions — say, from an injury or inflammation.

- too much body fat and/or not enough lean mass.

- too many or too few calories/nutrients to feel energetic.

- age-related loss of mobility.

- a physical disability.

- neurological problems.

You may have some body configuration that makes it easier or harder for you to do certain things.

We all have structural or physical limitations. We all have advantages. It all depends on context.

Regardless of what your unique physical makeup might be, there are activities that can work for you, and help you make movement a big part of your daily life.

Ask yourself:

How can I move better — whatever that means for MY unique body? And what might my life be like if I did?

And finding someone who can help you if you think that’s what you need.

What to do next

1. Pay attention to how it feels to move.

“Sense in” to your body:

- When you walk or run: How long is your stride? Do your legs swing freely? Do your hips feel tight or loose? What are your arms doing? Where are you looking?

- When you stand: How does your weight shift gently as you stand? What does that feel like in your feet or lower legs?

- When you sit: Where is your head? Can you feel the pressure of the seat on your back or bottom?

- When you work out: Can you feel the muscles working? What happens if you try to do a fast movement (like a jump or kick) slowly, and vice versa?

2. Consider whether you’re moving as well as you could.

Do you feel confident and capable? Ninja-ready for anything?

Do you have some physical limitations? Do you have ways to adapt or route around them?

When was the last time you tried learning new movement skills?

What movements would you like to try… in a perfect world?

3. Think about other ways to move.

If you’re working out a certain way because you think you “should”, but it’s not fitting your body well, consider other options.

Or, if your current workout is going great but you’re curious about other possibilities, consider expanding your movement repertoire anyway.

Everything from archery to Zumba is out there, waiting for you to come and try it out.

Remember: You don’t have to “work out” or “exercise” to move. And you don’t need to revamp your physical activity overnight, either.

Take your time. Do what you like. Pick one small new way you can move today — and do it.

4. Help your body do its job with good nutrition.

Quality movement requires quality nutrition.

And just like your movements, your nutritional needs are unique to you.

Here’s how to start figuring out what “optimal nutrition” means for you:

- Balance your intake to eliminate possible nutrient deficiencies.

- Calibrate your calorie intake with easy, effective portion control andappetite awareness.

- Tailor your diet for special circumstances, like pregnancy or injury.

- Find ways to reduce stress (this may look a bit different for men andwomen).

If you feel like you need help on these fronts, get it.

A good fitness and nutrition coach can:

- help you find activities that suit your body.

- review your nutrition and offer advice on how to improve your diet (even if your life is hectic).

- help you identify any potential food sensitivities that could be causing or worsening inflammation and thus restricting your movements.

For full article by Krista Scott-Dixon, please visit http://www.precisionnutrition.com/healthy-movement

While the mainstay of chiropractic is spinal manipulation, chiropractic care now includes a wide variety of other treatments, including manual or manipulative therapies, postural and exercise education, ergonomic training (how to walk, sit, and stand to limit back strain), nutritional consultation, and even ultrasound and laser therapies. In addition, chiropractors today often work in conjunction with primary care doctors, pain experts, and surgeons to treat patients with pain.

While the mainstay of chiropractic is spinal manipulation, chiropractic care now includes a wide variety of other treatments, including manual or manipulative therapies, postural and exercise education, ergonomic training (how to walk, sit, and stand to limit back strain), nutritional consultation, and even ultrasound and laser therapies. In addition, chiropractors today often work in conjunction with primary care doctors, pain experts, and surgeons to treat patients with pain.